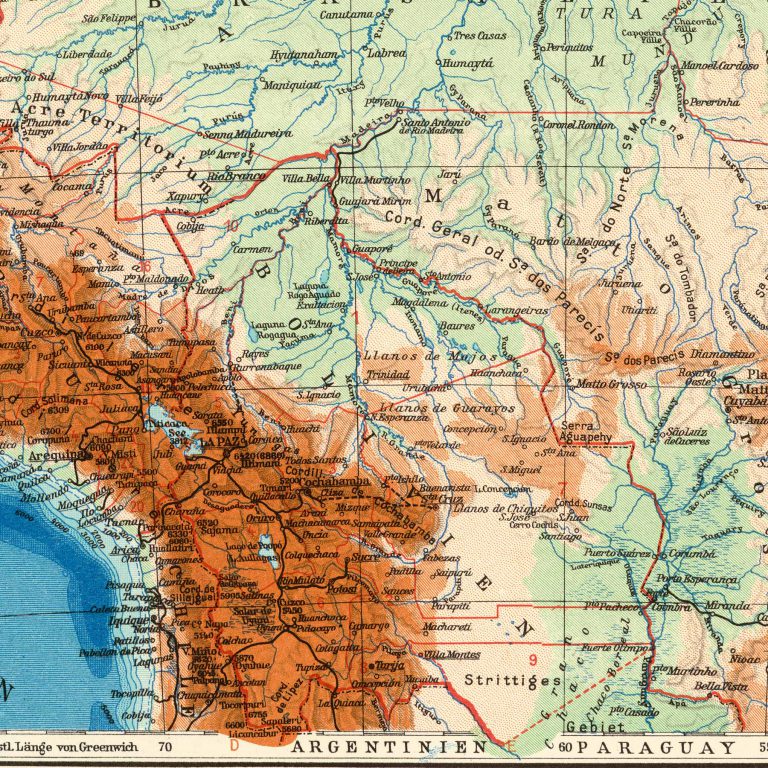

Bolivia

Policy on Immigration and Refugees

In the first half of the 20th century, Bolivia is one of the poorest countries in Latin America and is considered an unattractive destination for immigrants. The indigenous population lives under conditions similar to serfdom. A middle class, labor unions and a modern national market take shape only slowly. Foreign trade is completely dependent on tin production. In the Chaco War (1932–1935), 52,000 Bolivians are killed. The country’s defeat by Paraguay leads to tremendous territorial losses and foreign debts, as well as political instability. Bolivia is ruled by the military until Germán Busch, the son of a German doctor, assumes the presidency in July 1937.

In the hope of stimulating the stagnant Bolivian economy, in June 1938 the government offers unlimited immigration for agricultural workers. The German Jewish industrialist Moritz Hochschild, who plays an important role in the immigration of Jews to Bolivia, supports the issuance of such visas. In January 1939, in cooperation with the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, he founds the Sociedad de Protección a los Imigrantes Israelitas/SOPRO (Society for the Protection of Jewish Immigrants). He sponsors a settlement project in the undeveloped lowlands that is intended to enable larger groups of Jewish refugees to immigrate there.

The country’s liberal immigration policies, however, do not go unchallenged. Rumors about a trade in blank visas and uncontrolled immigration by Jewish refugees without agricultural qualifications lead to political upheaval. More restrictive immigration rules are passed but not consistently enforced. Antisemitic hostility increases.

Nonetheless, by the beginning of World War II, Bolivia develops into one of the main Latin American countries taking in Jewish refugees – until April 1940, when the Bolivian government passes a law forbidding all Jewish immigration indefinitely and without exception.

In total, about 8,000 German and Austrian Jews are able to save themselves by going to Bolivia.

Paraguayan soldiers with Bolivian prisoners of war during the Chaco War, January 1935

Rumors that Paraguay wants to settle the territories that Bolivia lost in the Chaco War with Jewish refugees stoke suspicion toward both refugees and the country’s liberal immigration policies.

SZ Photo, München

Paraguayan soldiers with Bolivian prisoners of war during the Chaco War, January 1935

Rumors that Paraguay wants to settle the territories that Bolivia lost in the Chaco War with Jewish refugees stoke suspicion toward both refugees and the country’s liberal immigration policies.

SZ Photo, München

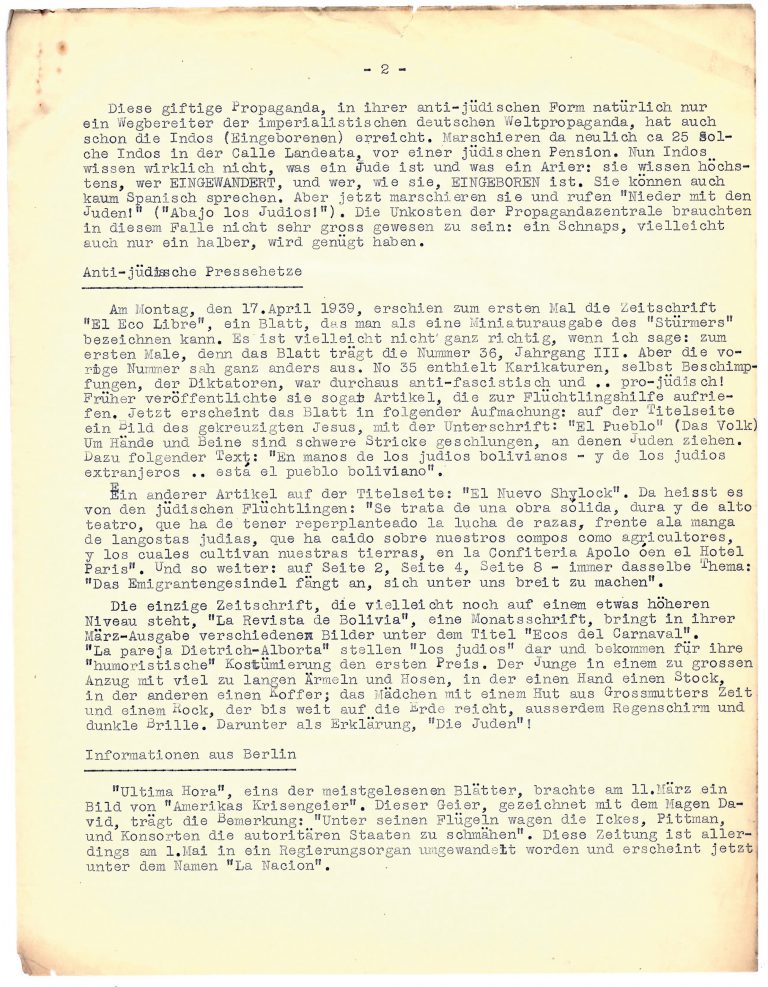

Eyewitness report on “anti-Jewish agitation in the press” in Bolivia, ca. 1939

The Wiener Library for the Study of the Holocaust & Genocide, London

Eyewitness report on “anti-Jewish agitation in the press” in Bolivia, ca. 1939

The Wiener Library for the Study of the Holocaust & Genocide, London

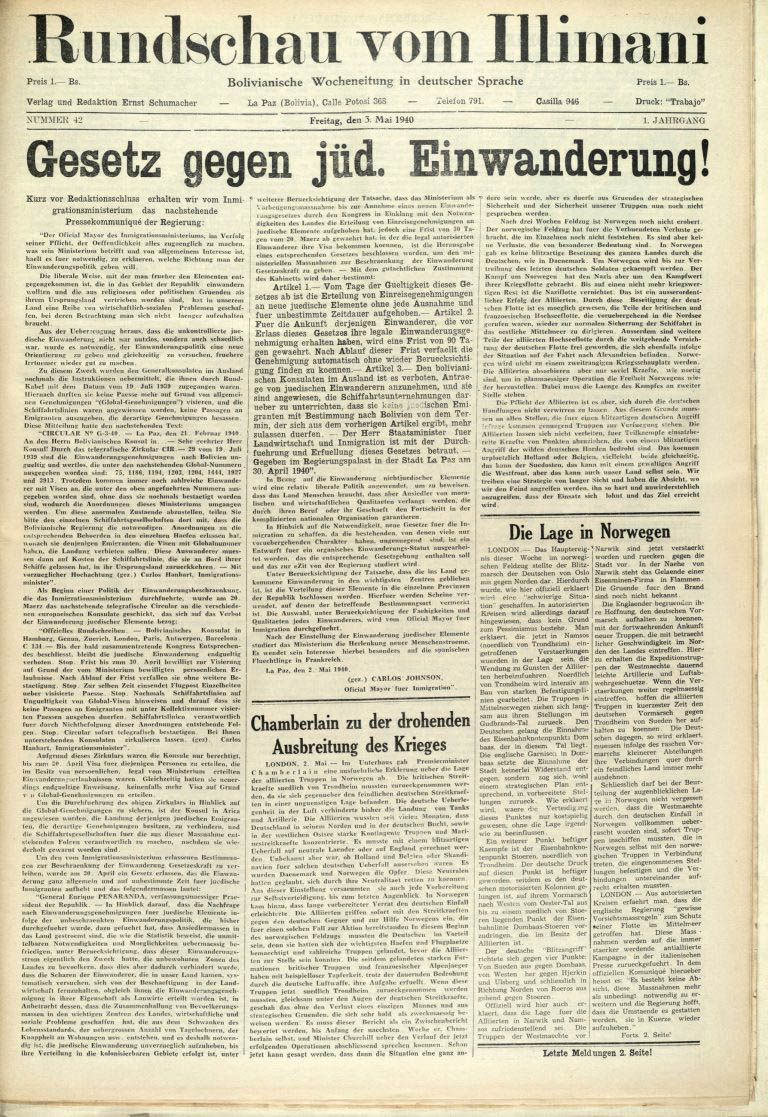

Article on the end of liberal immigration policies, in the German-language Bolivian publication Rundschau vom Illimani, May 3, 1940

The immigration law of April 30, 1940, specifically and exclusively targets Jewish refugees. “A liberal policy is applied to immigration by non-Jewish elements,” reports the weekly newspaper Rundschau vom Illimani, which is published by German Social Democrats in Bolivia.

Verlag Ernst Schumacher, La Paz

Article on the end of liberal immigration policies, in the German-language Bolivian publication Rundschau vom Illimani, May 3, 1940

The immigration law of April 30, 1940, specifically and exclusively targets Jewish refugees. “A liberal policy is applied to immigration by non-Jewish elements,” reports the weekly newspaper Rundschau vom Illimani, which is published by German Social Democrats in Bolivia.

Verlag Ernst Schumacher, La Paz

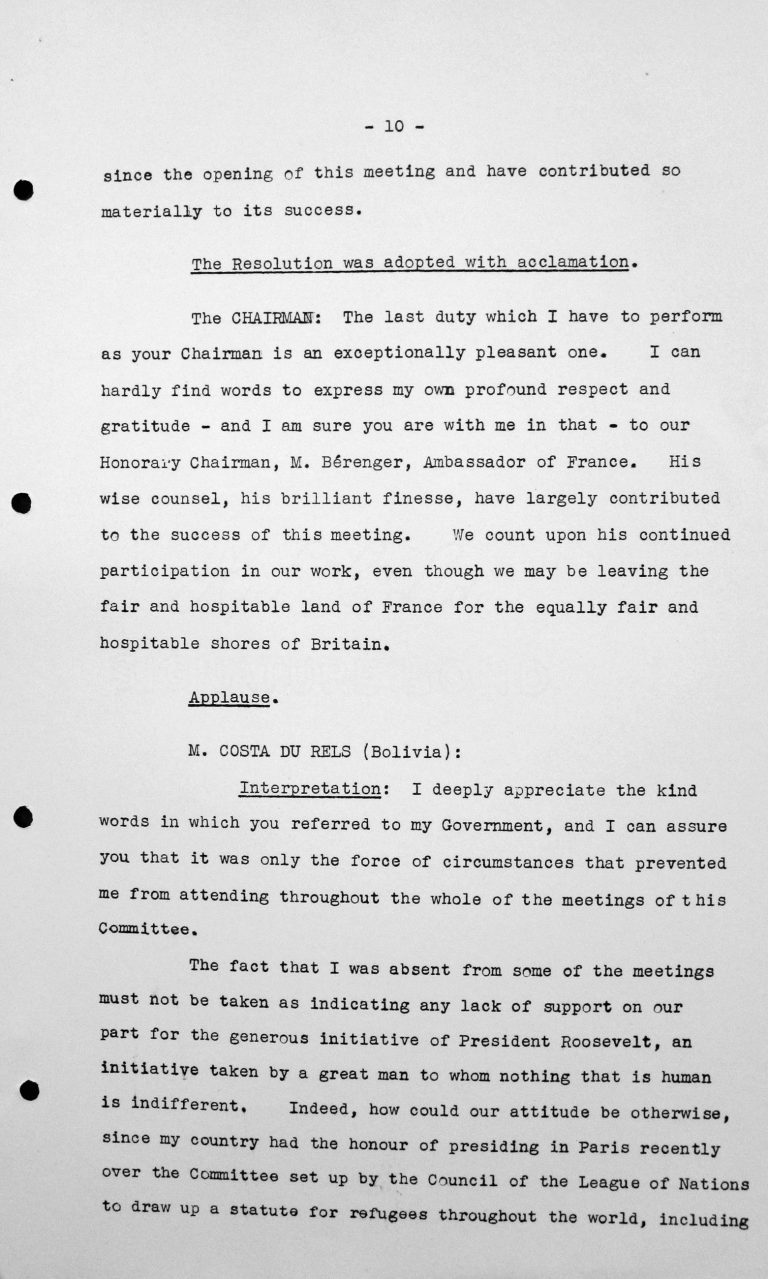

Delegation

Adolfo Costa du Rels

* 19 June 1891 Sucre † 1980

The son of a French father and a Bolivian mother, Adolfo Costa du Rels grows up in France, where he studies literature and law. In 1912, Costa du Rels returns to Bolivia. He quickly amasses a large fortune in the oil business.

In 1917, he enters the diplomatic service, and in 1930 is appointed the Bolivian delegate to the League of Nations. At the same time, Costa du Rels pursues a career as a writer. In poetry, plays and prose, he criticizes the exploitation of the indigenous population and the privileges of the Bolivian elites. His diplomatic efforts in the Chaco War fail.

At the start of 1938, he becomes involved in the negotiations of the Nansen International Office for Refugees, seeking to make Bolivia a possible country of refuge for German Jews. He does not take part in the Évian Conference from the outset.

Adolfo Costa du Rels, undated

Photo: C. Ed. Boesch / United Nations Archives, Genf

Adolfo Costa du Rels, undated

Photo: C. Ed. Boesch / United Nations Archives, Genf

Simón Iturri Patiño

* 1 June 1862 Cochabamba † 20 April 1947 Buenos Aires

Simon Patiño grows up in humble circumstances. He serendipitously ends up owning an extremely profitable tin mine. By 1905 he owns Bolivia’s largest mining group, and by 1906 he also owns its largest bank. Patiño has direct access to the president and all of the country’s political institutions.

In 1911 he turns down the Liberal Party’s offer for him to represent them in the Senate, and in 1920 he likewise turns down the Republican Party’s offer of its presidential candidacy. His political interests and influence primarily concern the expansion of the mining industry. Patiño controls the world’s largest tin mining group and is considered the richest man in the world.

In 1923, he makes Paris his main place of residence; in France he holds the office of minister plenipotentiary. It is in this capacity that he takes part in the Évian Conference, albeit without speaking publicly there.

Simón Iturri Patiño, undated painting by Avelino Nogales

Fundación Universitaria Simon Patiño, Cochabamba

Simón Iturri Patiño, undated painting by Avelino Nogales

Fundación Universitaria Simon Patiño, Cochabamba

Conference Contributions

Speech by Adolfo Costa du Rels (Bolivia) in the public session on July 15, 1938, 11am, p. 1/3

Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, NY

Speech by Adolfo Costa du Rels (Bolivia) in the public session on July 15, 1938, 11am, p. 1/3

Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, NY

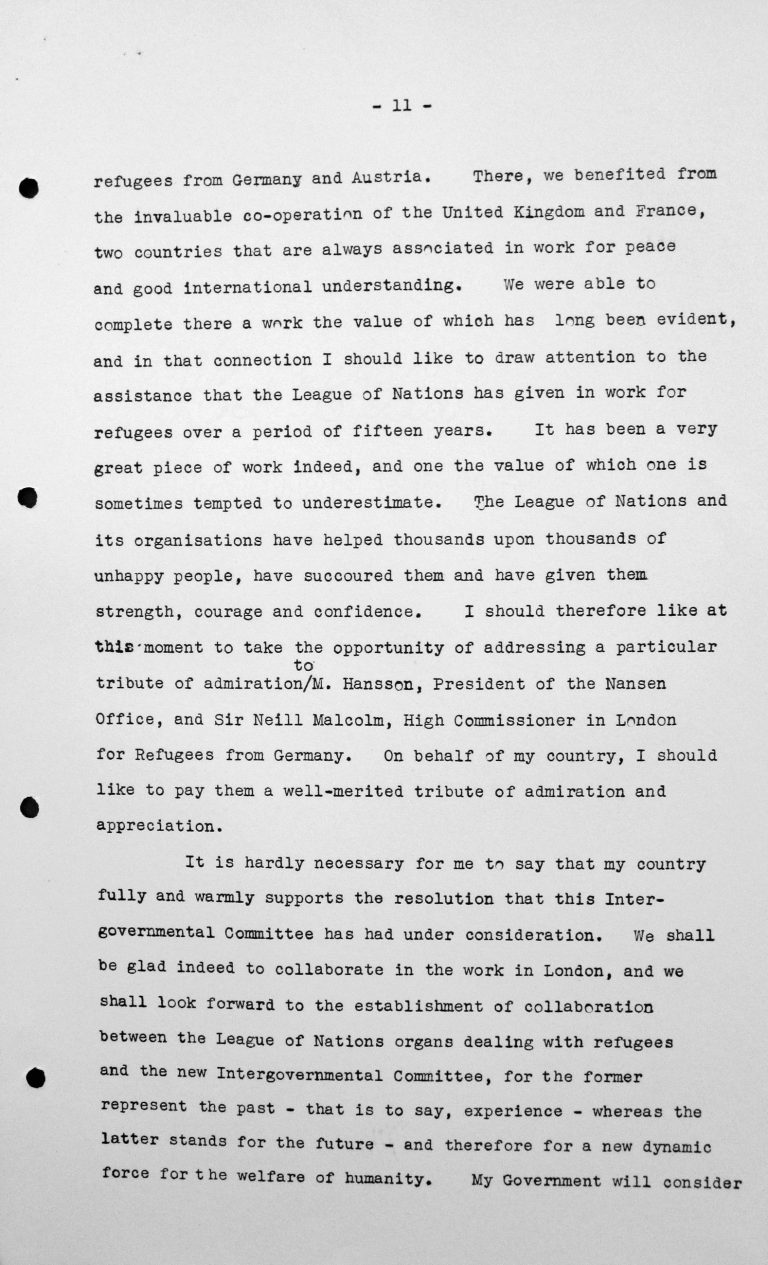

Speech by Adolfo Costa du Rels (Bolivia) in the public session on July 15, 1938, 11am, p. 2/3

Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, NY

Speech by Adolfo Costa du Rels (Bolivia) in the public session on July 15, 1938, 11am, p. 2/3

Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, NY

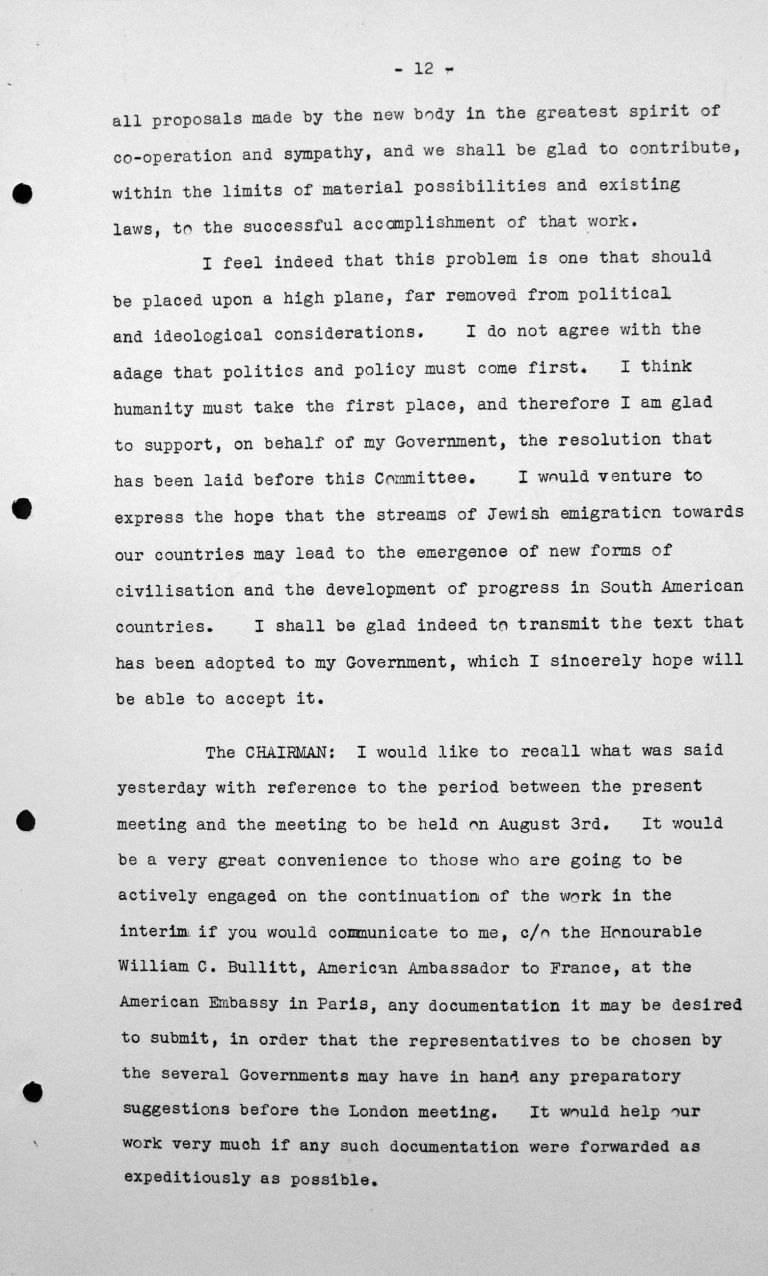

Speech by Adolfo Costa du Rels (Bolivia) in the public session on July 15, 1938, 11am, p. 3/3

Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, NY

Speech by Adolfo Costa du Rels (Bolivia) in the public session on July 15, 1938, 11am, p. 3/3

Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, NY