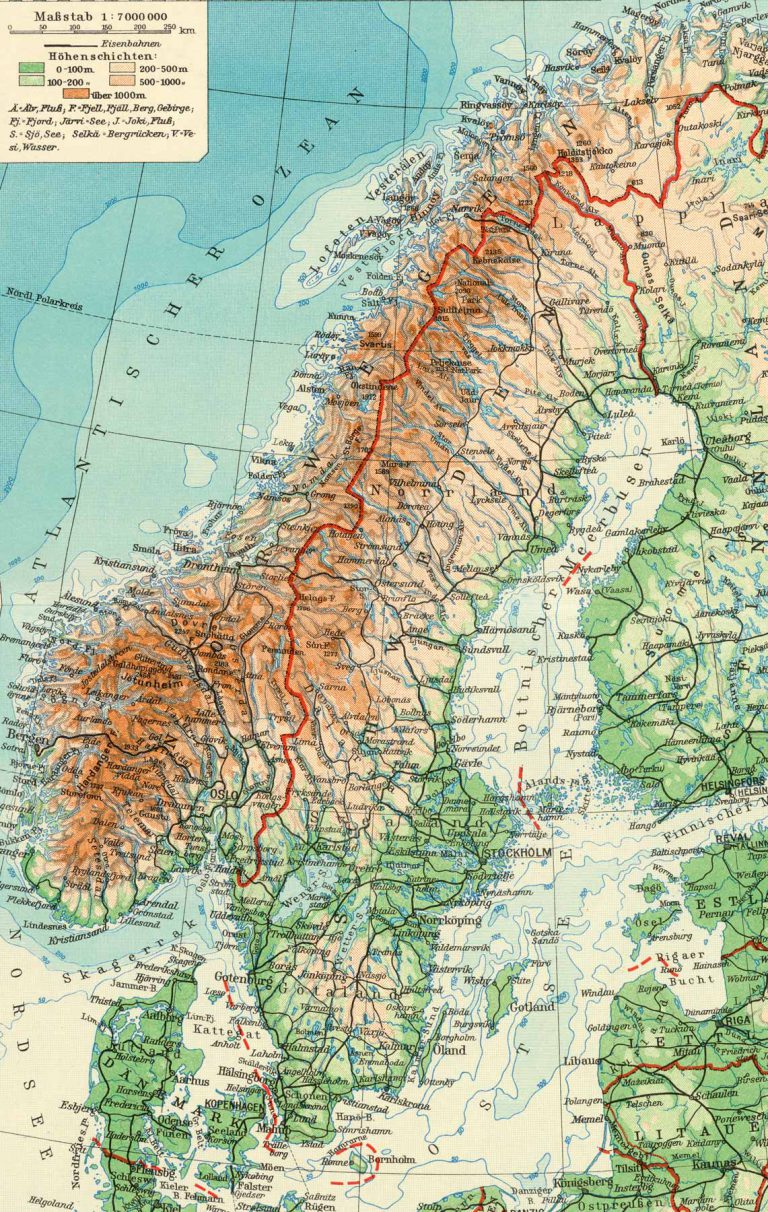

Sweden

Policy on Immigration and Refugees

Since 1880, the Kingdom of Sweden has pursued a protectionist immigration policy, both to shield the labor market from foreign competition and defend the “Swedish race” against “foreign infiltration.” Xenophobia and antisemitism receive broad public support. This is reflected in legislation as well as in public discourse, where the expression “Sweden for Swedes” is popular. During the Great Depression of 1929–1932, unemployment rises to 23 percent in this Scandinavian country. In response, the “Aliens Act” of 1927 is extended for another five years in 1932: It imposes a passport obligation and gives provincial and local police authorities extensive powers regarding whether arriving foreigners are accepted, expelled or interned pending a decision.

Following a revision of the law in 1936/37, the Utlänningsbyrån (foreigner section) of the Socialstyrelse (social welfare authority) increasingly takes over the tasks of the local police authorities, deciding on residence and work permits. Visas are generally issued only after work permits have been granted; they in turn are issued primarily to highly qualified workers. Only a very small number of German Jews immigrate to Sweden in the 1930s. Like Switzerland, Sweden accepts the German stamping of Jews’ passports with the red “J” in 1938. In this way, “non-Aryans” can be identified more quickly and rejected at the border.

Sweden’s declaration of neutrality at the beginning of World War II does not prevent the Kingdom from maintaining economic relations with the German Reich. Nevertheless, immigration policy is liberalized in the early 1940s. In 1942, the Kingdom authorizes the entry of 900 Jews from Norway. In October 1943 Sweden grants asylum to 8,000 Jewish refugees who have fled occupied Denmark, crossing to Sweden via Öresund and Kattegat and Bornholm Island in small fishing boats.

Between 1933 and 1945, about 4,000 Jewish refugees from Germany and Austria end up in Sweden.

Escaping from Norway to Sweden

Watercolor painting by Dodo Kroner from April 9, 1940

Jüdisches Museum Berlin

Escaping from Norway to Sweden

Watercolor painting by Dodo Kroner from April 9, 1940

Jüdisches Museum Berlin

Delegation

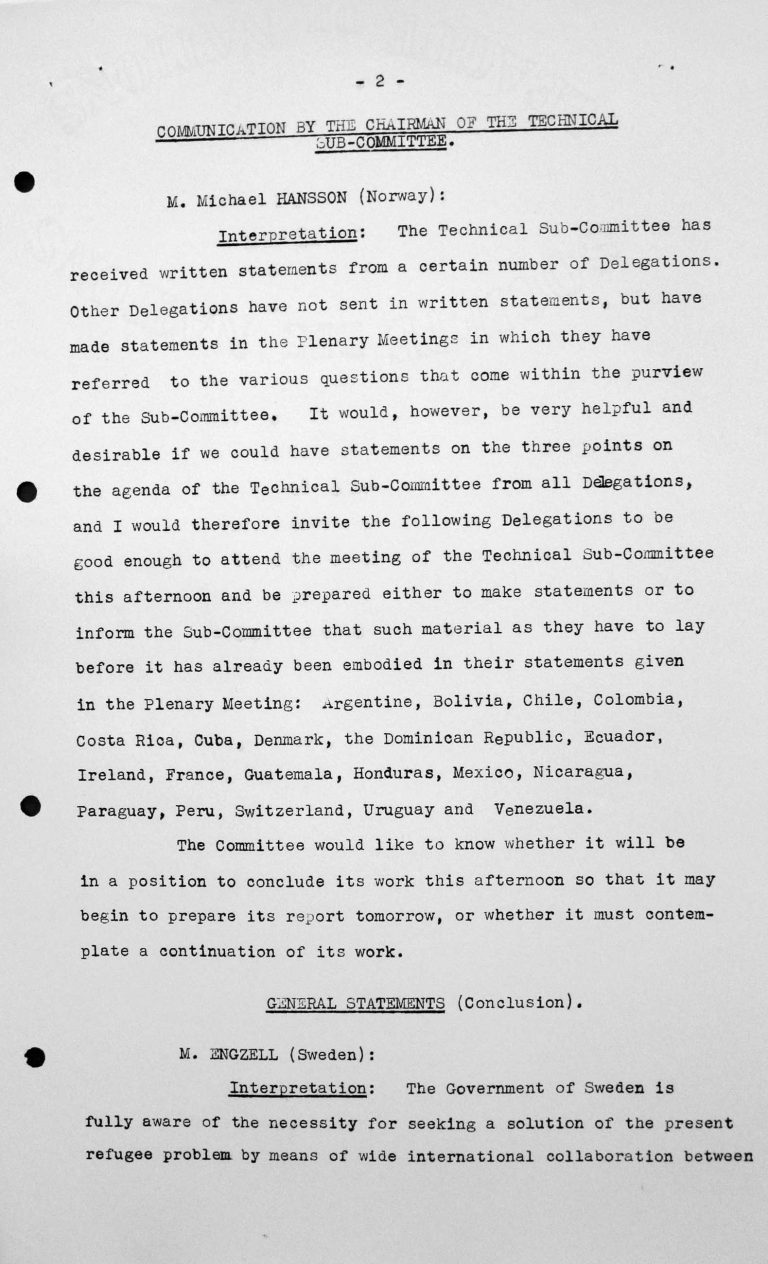

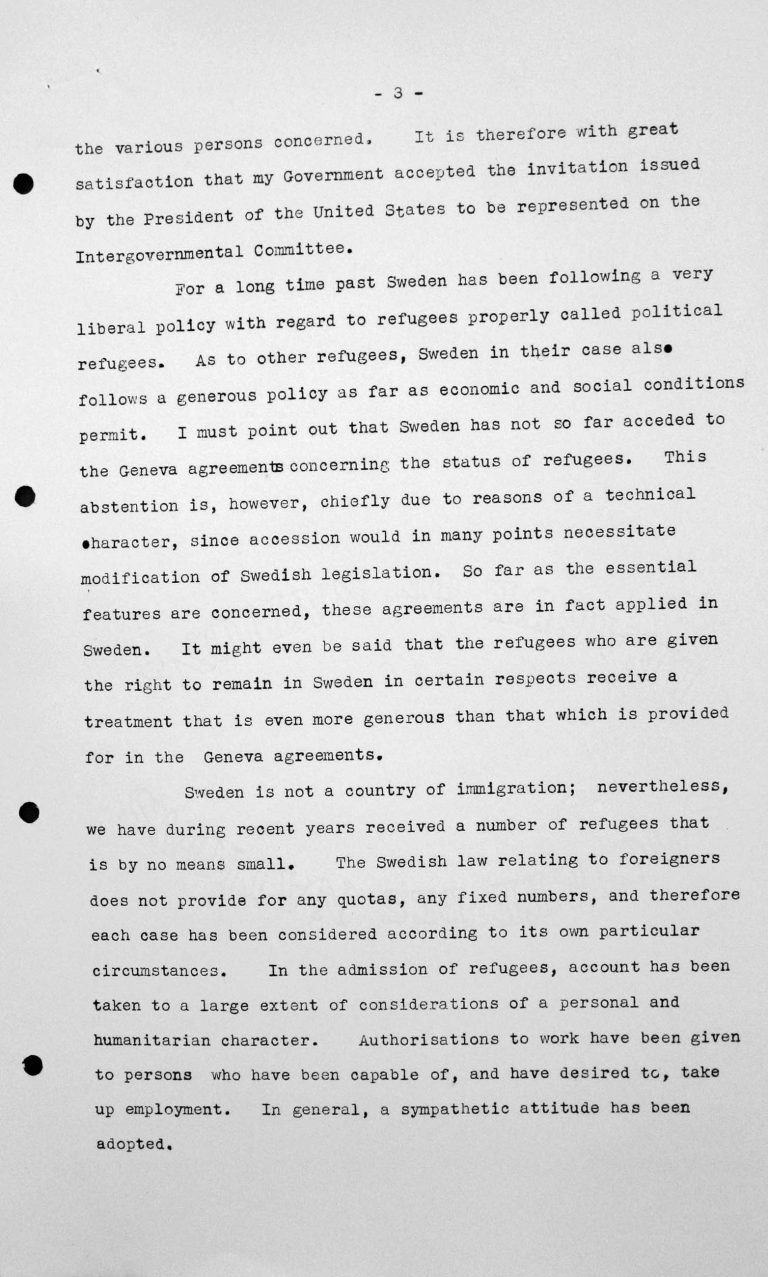

Gösta Engzell

* 14 February 1897 Halmstad † 7 March 1997 Stockholm

After studying law in Stockholm, Gösta Engzell begins his career in 1921 as secretary at the Court of Appeals in Jönköping; he is eventually promoted to court officer. In 1932 he becomes a department head at the Ministry of Commerce; in 1936 he takes on the same function at the Ministry of Finance. Finally, in 1938 he takes over directorship of the legal department of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which oversees Sweden’s refugee policy.

At first, this policy is restrictive towards Jewish refugees. This changes in 1942, as Engzell receives ever more reports from various sources about the genocide of European Jewry. Now he uses diplomacy to try to save as many Jews as he can, and is Raoul Wallenberg’s contact at the Foreign Ministry during his rescue mission in Budapest in 1944.

In 1947 Engzell is appointed envoy to Poland, where he then serves as ambassador from 1949 to 1951. This is followed by his appointment as ambassador to Finland, where he remains through 1963.

Gösta Engzell

Social-Demokraten, 15. Juli 1938/ Riksarkivet, Stockholm

Gösta Engzell

Social-Demokraten, 15. Juli 1938/ Riksarkivet, Stockholm

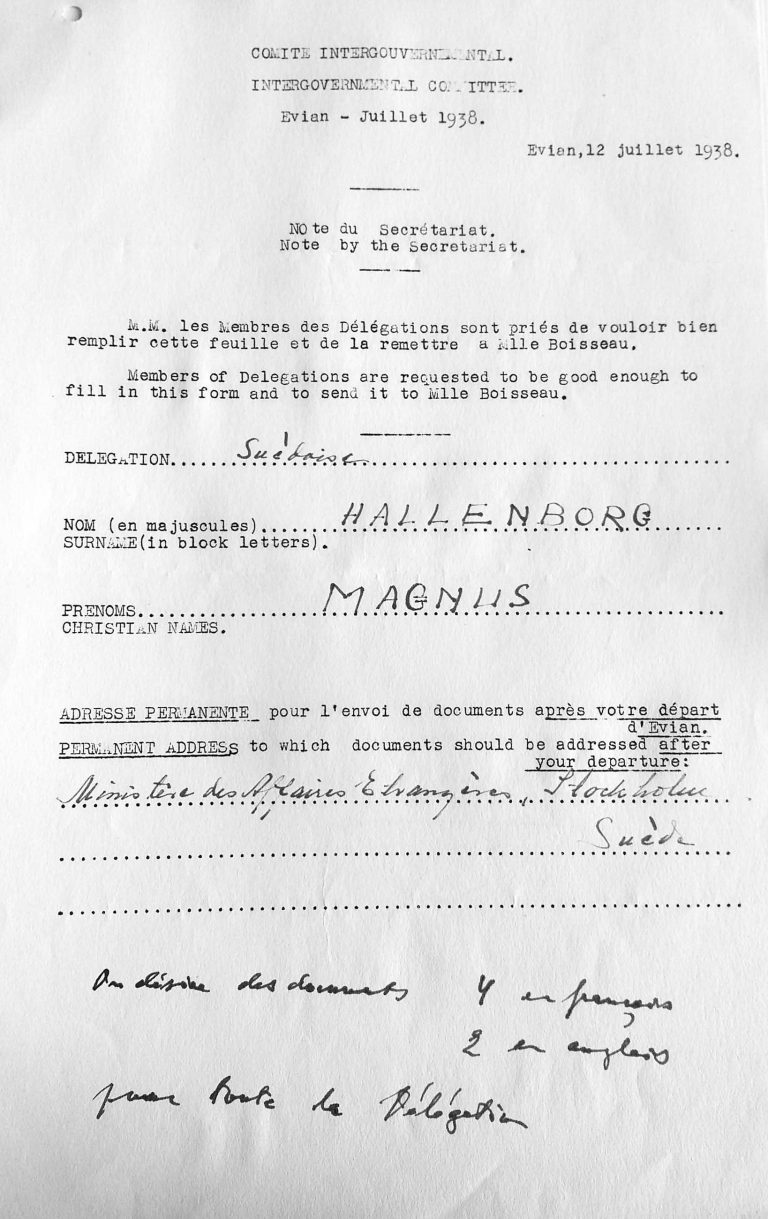

Carl Albert Magnus Hallenborg

* 26 March 1894 Stockholm † 22 November 1980 Lidingö

Carl Albert Magnus Hallenborg is born into an old Swedish noble family. His father is a hussar officer and, from 1928 until his death in 1934, court stable master. After studying law in Stockholm, Carl Albert Magnus Hallenborg enters the diplomatic corps in 1917 and ultimately serves as an attaché in the Swedish consulates in Lübeck, Chicago and Antwerp, then as vice-consul in Antwerp and Rotterdam, and as delegation secretary in Brussels and London.

In 1932 he is sent as a consul to Minneapolis, Minnesota, which is home to many immigrants from Sweden. In 1933 he becomes engaged to the English teacher Helen Thompson, whom he later marries. In 1934 he is transferred to the Swedish Embassy in Helsinki, where he serves as first legation secretary. He returns to the Swedish Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 1937 as ministerial councilor.

In 1944 Hallenborg moves to Bombay as consul general; in 1948 he is transferred to Antwerp and a year later to London.

Carl Albert Magnus Hallenborg, ca. 1932 in Minneapolis

Svenska amerikanska posten, 5. Juli 1933 / Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul, MN

Carl Albert Magnus Hallenborg, ca. 1932 in Minneapolis

Svenska amerikanska posten, 5. Juli 1933 / Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul, MN

Conference registration form for Carl Albert Magnus Hallenborg, July 12, 1938

United Nations Archives, Genf

Conference registration form for Carl Albert Magnus Hallenborg, July 12, 1938

United Nations Archives, Genf

Conference Contributions

Statement by Gösta Engzell (Sweden) in the public session on July 11, 1938, 11am, p. 1/5

Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, NY

Statement by Gösta Engzell (Sweden) in the public session on July 11, 1938, 11am, p. 1/5

Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, NY

Statement by Gösta Engzell (Sweden) in the public session on July 11, 1938, 11am, p. 2/5

Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, NY

Statement by Gösta Engzell (Sweden) in the public session on July 11, 1938, 11am, p. 2/5

Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, NY

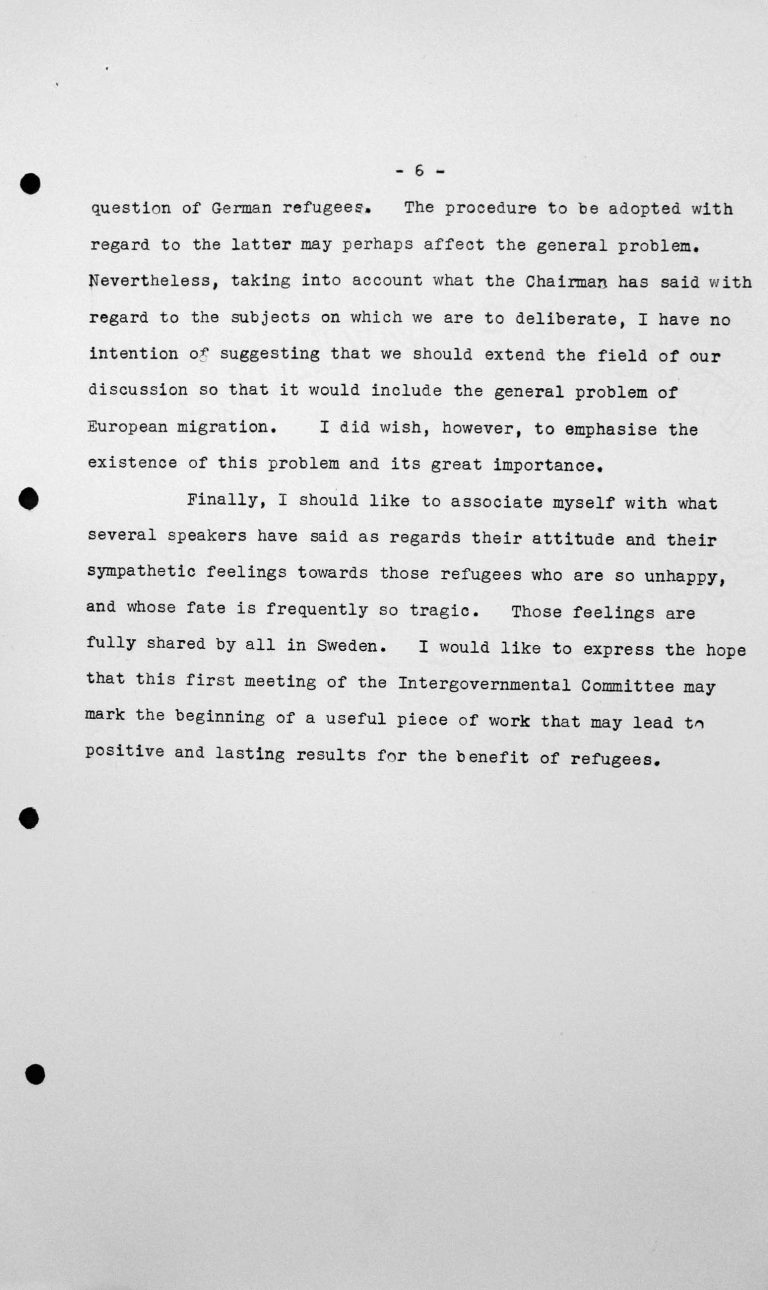

Statement by Gösta Engzell (Sweden) in the public session on July 11, 1938, 11am, p. 3/5

Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, NY

Statement by Gösta Engzell (Sweden) in the public session on July 11, 1938, 11am, p. 3/5

Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, NY

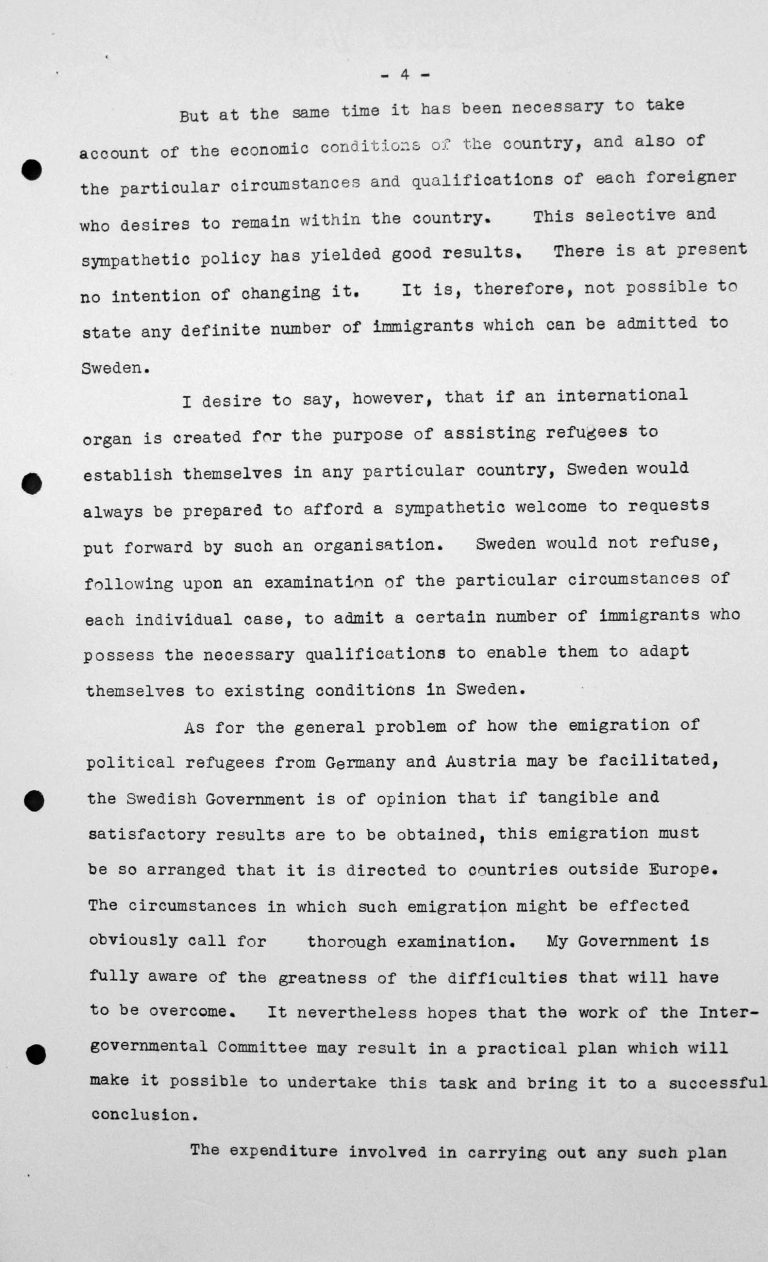

Statement by Gösta Engzell (Sweden) in the public session on July 11, 1938, 11am, p. 4/5

Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, NY

Statement by Gösta Engzell (Sweden) in the public session on July 11, 1938, 11am, p. 4/5

Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, NY

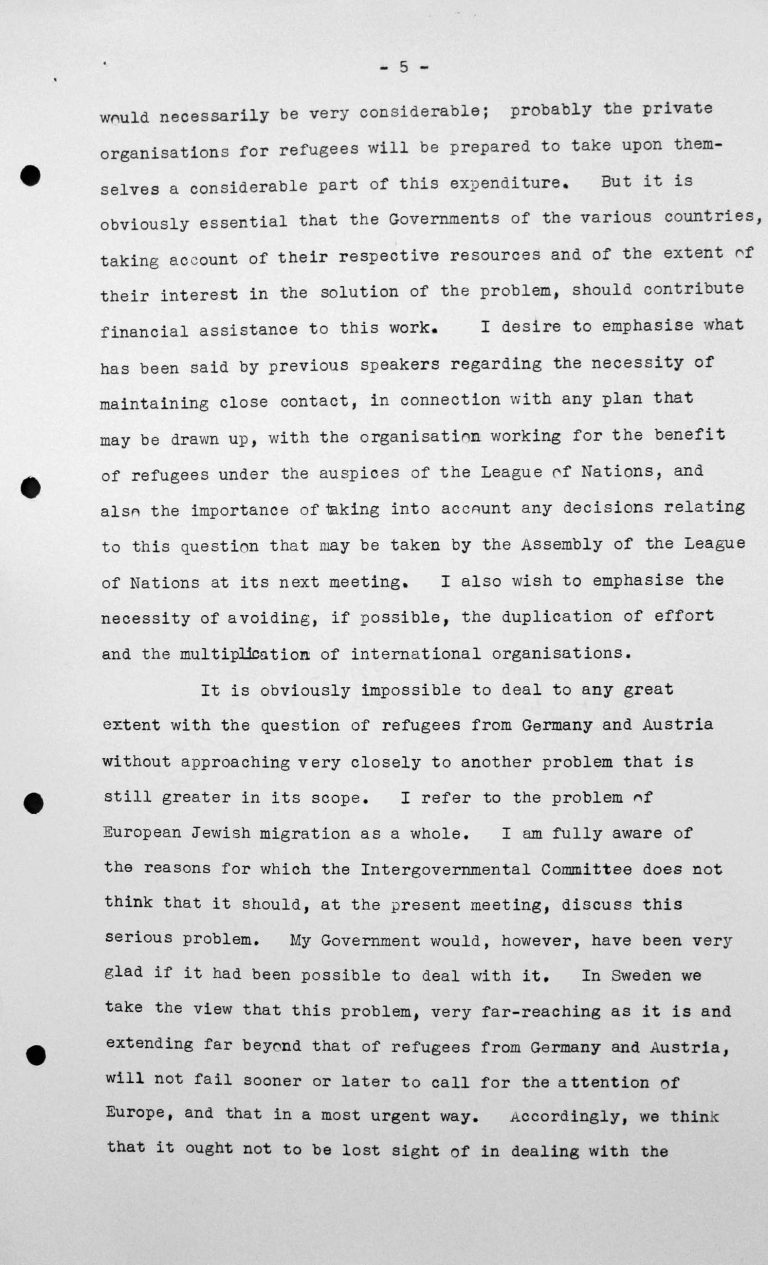

Statement by Gösta Engzell (Sweden) in the public session on July 11, 1938, 11am, p. 5/5

Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, NY

Statement by Gösta Engzell (Sweden) in the public session on July 11, 1938, 11am, p. 5/5

Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, NY

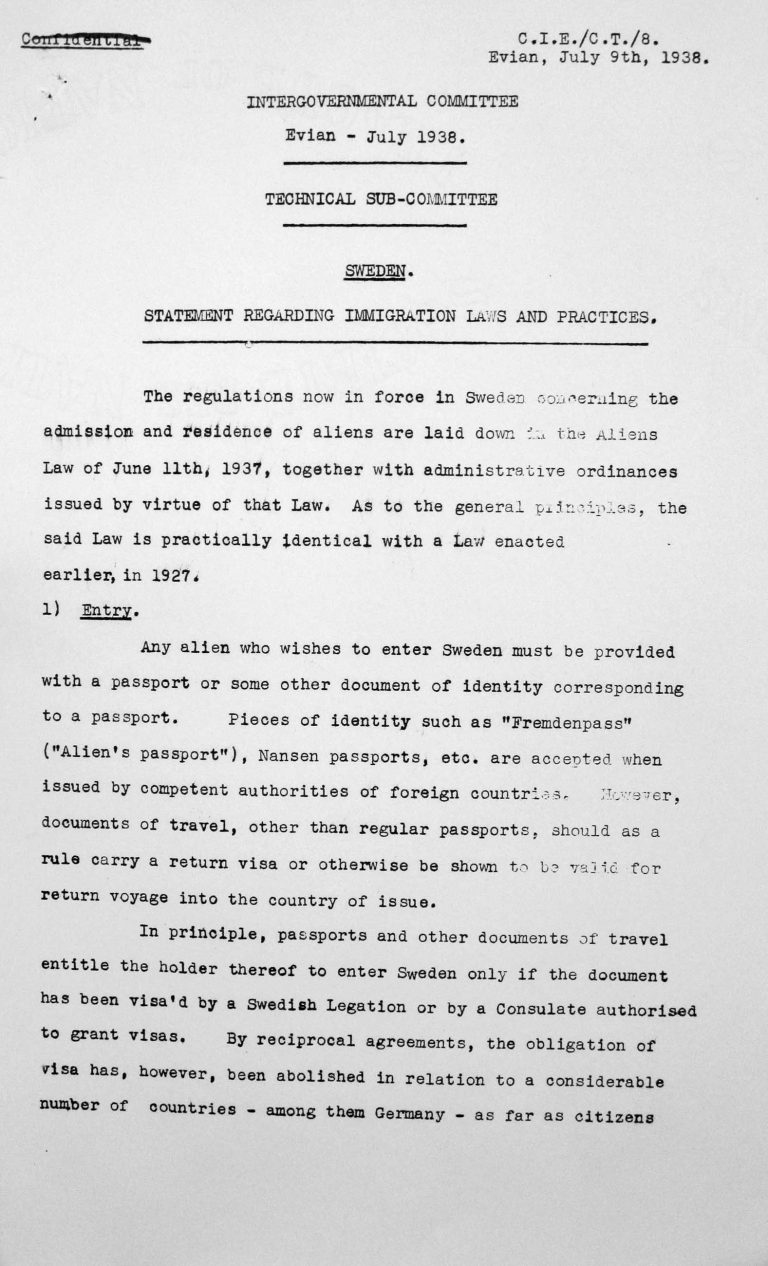

Statement of Sweden for the Technical Sub-Committee regarding immigration laws and practices, July 9, 1938, p. 1/5

Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, NY

Statement of Sweden for the Technical Sub-Committee regarding immigration laws and practices, July 9, 1938, p. 1/5

Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, NY

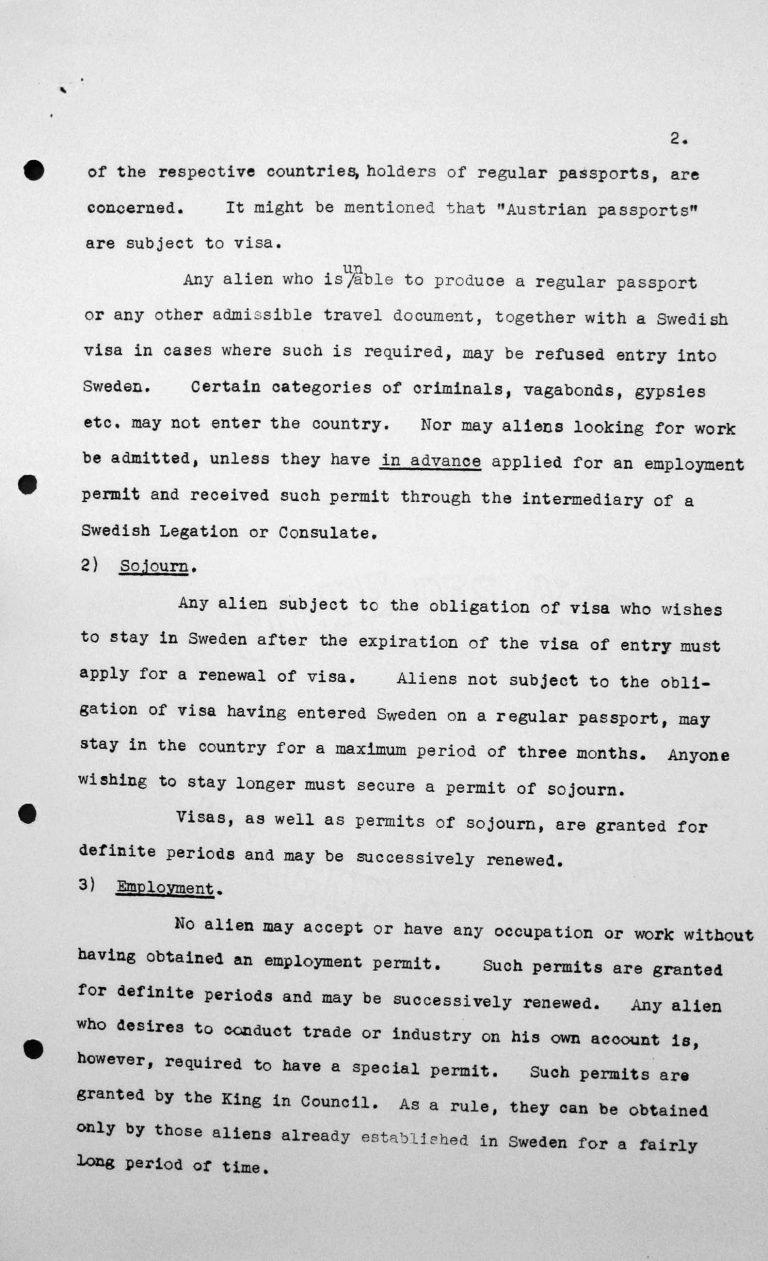

Statement of Sweden for the Technical Sub-Committee regarding immigration laws and practices, July 9, 1938, p. 2/5

Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, NY

Statement of Sweden for the Technical Sub-Committee regarding immigration laws and practices, July 9, 1938, p. 2/5

Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, NY

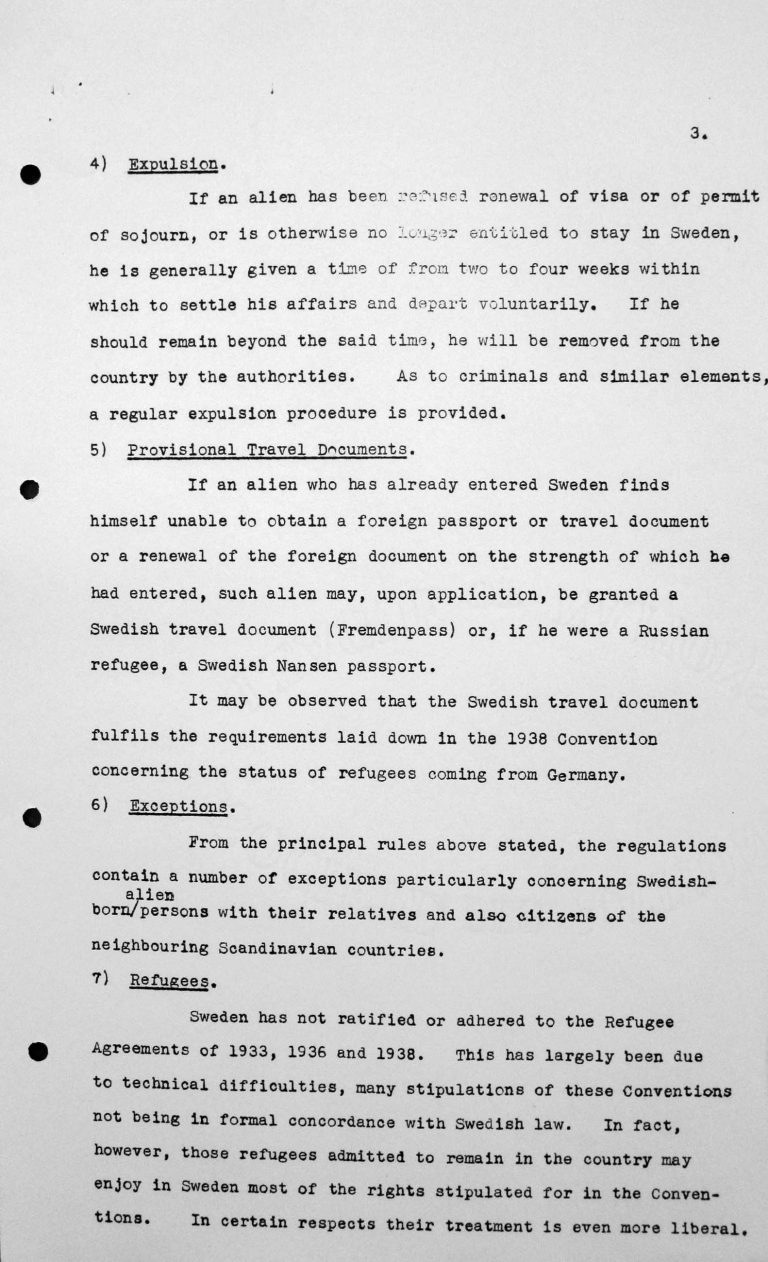

Statement of Sweden for the Technical Sub-Committee regarding immigration laws and practices, July 9, 1938, p. 3/5

Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, NY

Statement of Sweden for the Technical Sub-Committee regarding immigration laws and practices, July 9, 1938, p. 3/5

Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, NY

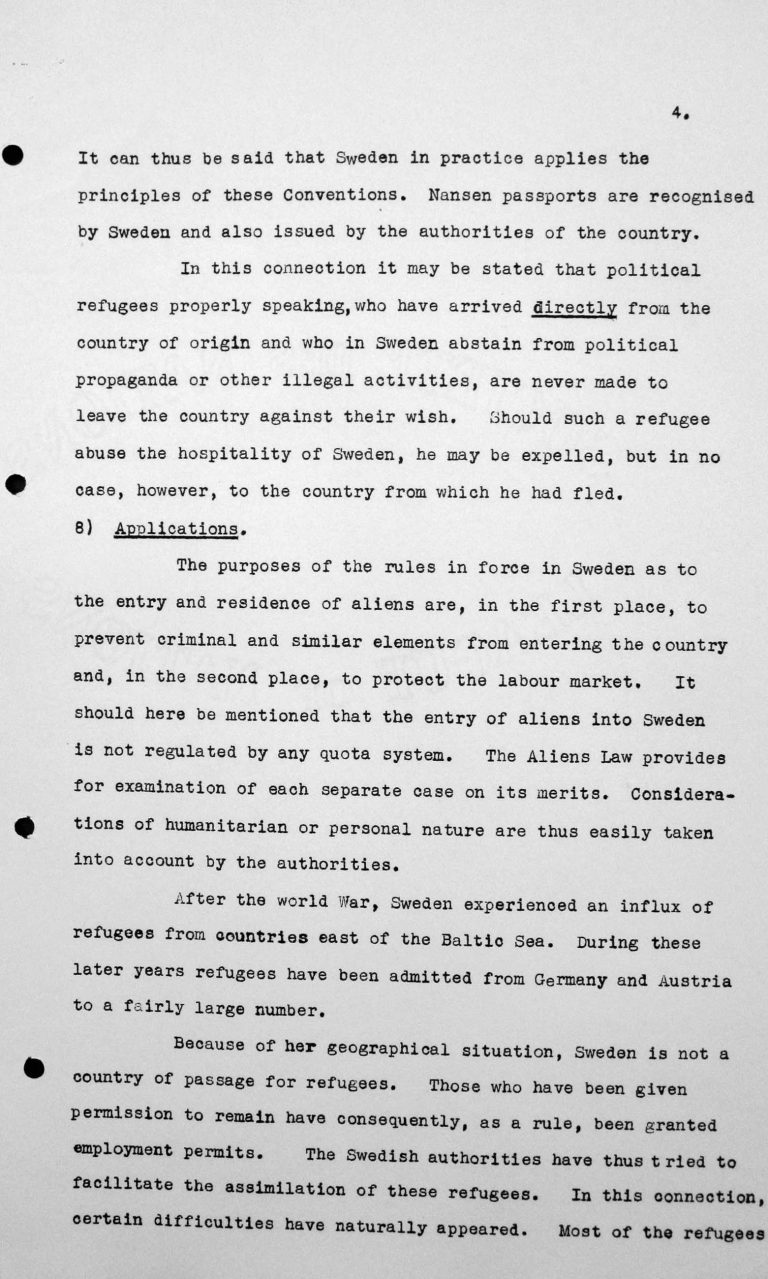

Statement of Sweden for the Technical Sub-Committee regarding immigration laws and practices, July 9, 1938, p. 4/5

Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, NY

Statement of Sweden for the Technical Sub-Committee regarding immigration laws and practices, July 9, 1938, p. 4/5

Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, NY

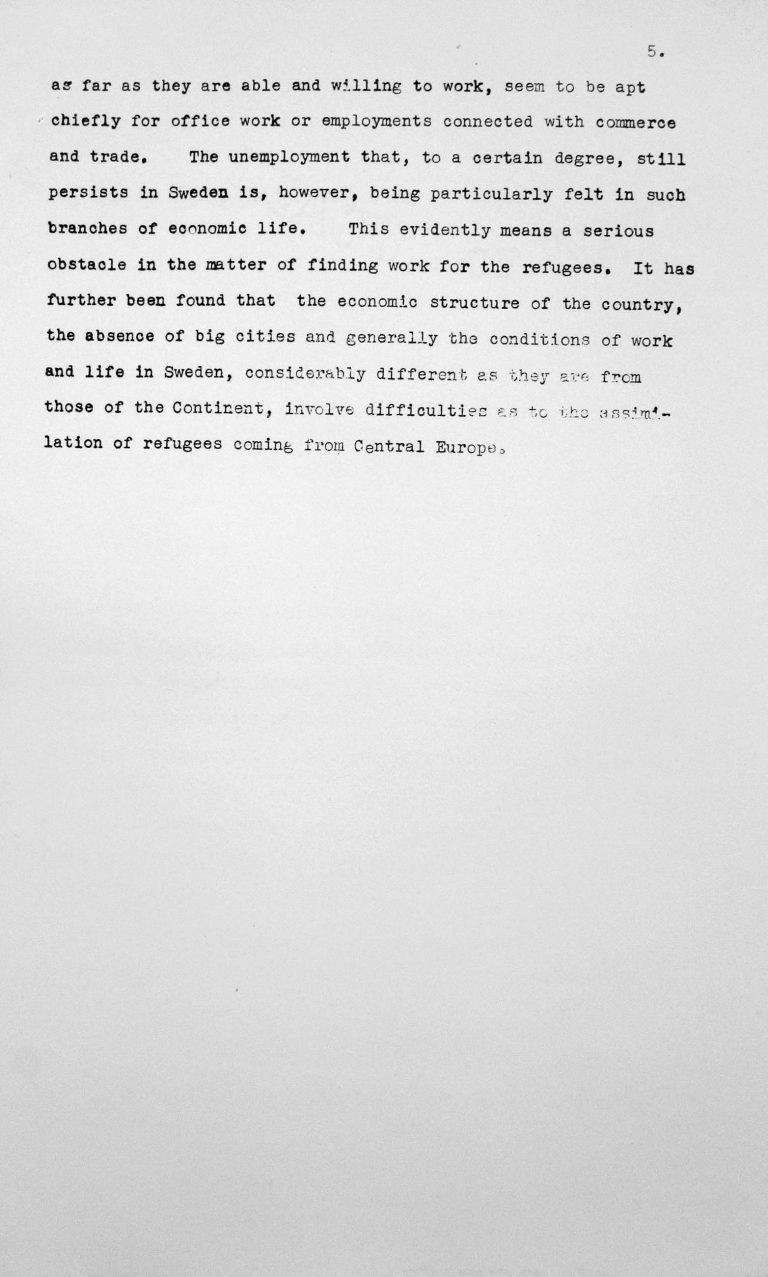

Statement of Sweden for the Technical Sub-Committee regarding immigration laws and practices, July 9, 1938, p. 5/5

Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, NY

Statement of Sweden for the Technical Sub-Committee regarding immigration laws and practices, July 9, 1938, p. 5/5

Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, NY