A Kibbutz in a Caribbean Dictatorship

At the conference, the Dominican delegate, like many of his colleagues from Latin America, states that his country will only allow agricultural workers to enter. It is not until August 12, 1938 that the dictator Rafael Leonidas Trujillo makes the surprising offer to “immediately” take “50,000 to 100,000 involuntary emigrants.” Trujillo hopes this step will make others forget the mass killing of approximately 20,000 dark-skinned Haitian migrant workers the previous year. At the same time, he wishes to present himself as a humanitarian, to populate the poorly developed northern part of his country and, through marriages between the immigrants and locals, to “lighten” the skin color of the general population.

After initial skepticism about this offer, the Intergovernmental Committee and the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee see that possible settlement areas are reviewed. The experts recommend Sosúa on the northern coast of the Dominican Republic as a suitable site. With the support of the US State Department, their clients then establish the Dominican Republic Settlement Association (DORSA).

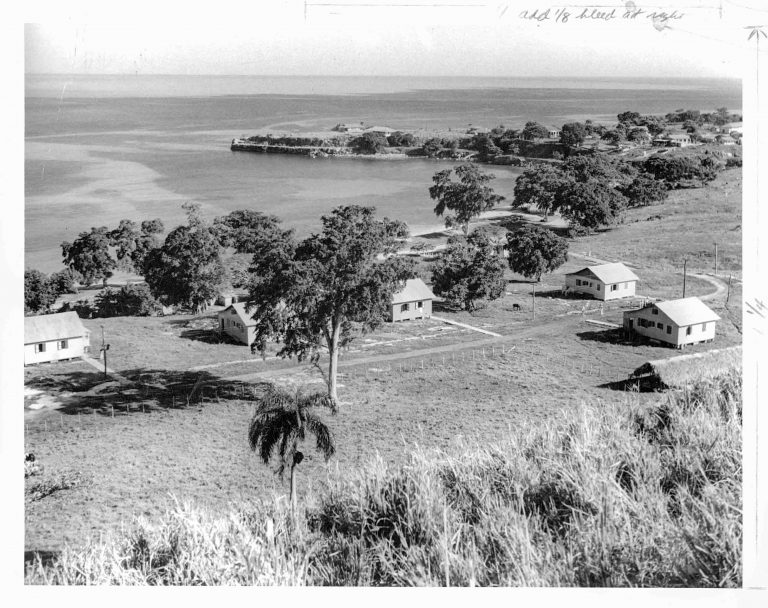

The Jewish Settlement on the bay of Sosúa, 1940

Using donated funds, DORSA purchases land for the settlement in Sosúa, takes over the selection of settlers in Europe and organizes their passage to the Dominican Republic. After the founding of the Sosúa Settlement in 1940, about 500 families from Central Europe settle there. Overall, instead of the 50,000–100,000 refugees mentioned in Trujillo’s offer, only about 3,000 find refuge in the Dominican Republic. For many of them, the island nation is only a transit station on the way to the US. However, some descendants of the settlers still live in Sosúa, which has developed into one of the country’s tourist centers.

Photo: Dr. Kurt Schnitzer, Photo Conrado, American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee Archives, New York, NY

The Jewish Settlement on the bay of Sosúa, 1940

Using donated funds, DORSA purchases land for the settlement in Sosúa, takes over the selection of settlers in Europe and organizes their passage to the Dominican Republic. After the founding of the Sosúa Settlement in 1940, about 500 families from Central Europe settle there. Overall, instead of the 50,000–100,000 refugees mentioned in Trujillo’s offer, only about 3,000 find refuge in the Dominican Republic. For many of them, the island nation is only a transit station on the way to the US. However, some descendants of the settlers still live in Sosúa, which has developed into one of the country’s tourist centers.

Photo: Dr. Kurt Schnitzer, Photo Conrado, American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee Archives, New York, NY

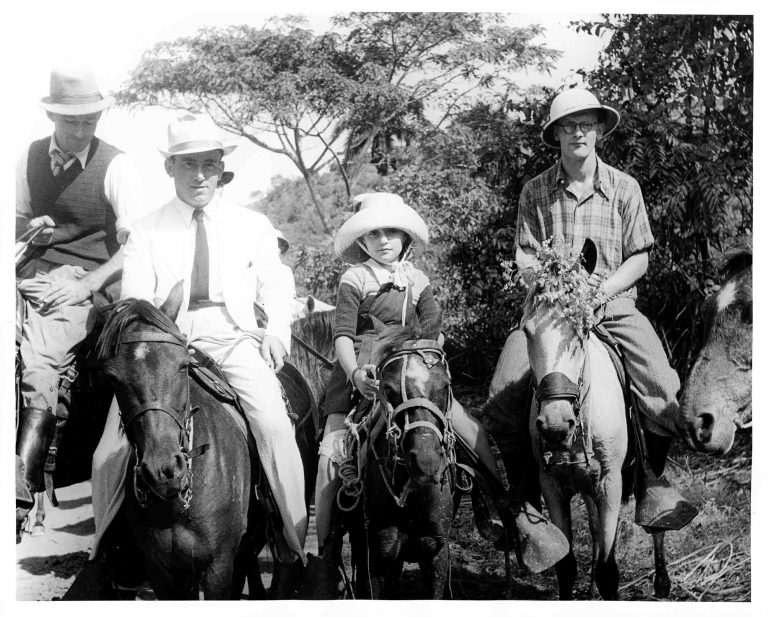

Sosúa settlers, 1940

Many of the settlers have only pretended to be skilled agricultural workers; in reality, they are doctors, lawyers, teachers or artists. Hence they not only have to adapt to another climate and language but also must prove their ability in entirely new occupations. Since most of them cling to the cultural traditions of their countries of origin, Sosúa becomes a little European-Jewish enclave in the Caribbean.

Photo: Dr. Kurt Schnitzer, Photo Conrado, American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee Archives, New York, NY

Sosúa settlers, 1940

Many of the settlers have only pretended to be skilled agricultural workers; in reality, they are doctors, lawyers, teachers or artists. Hence they not only have to adapt to another climate and language but also must prove their ability in entirely new occupations. Since most of them cling to the cultural traditions of their countries of origin, Sosúa becomes a little European-Jewish enclave in the Caribbean.

Photo: Dr. Kurt Schnitzer, Photo Conrado, American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee Archives, New York, NY

A Sosúa Settlement (SS) donkey cart, 1940

The Jewish settlers, most of whom have no experience in agricultural work, often must clear dense forests before they can plant fields. After a while, however, they build a functioning milk and meat business and brew schnapps in their own distillery. The Sosúa Settlement’s products become known and popular nationwide. In the settlement, medical care, schools and entertainment are organized according to the kibbutz principle.

Photo: Dr. Kurt Schnitzer, Photo Conrado, American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee Archives, New York, NY

A Sosúa Settlement (SS) donkey cart, 1940

The Jewish settlers, most of whom have no experience in agricultural work, often must clear dense forests before they can plant fields. After a while, however, they build a functioning milk and meat business and brew schnapps in their own distillery. The Sosúa Settlement’s products become known and popular nationwide. In the settlement, medical care, schools and entertainment are organized according to the kibbutz principle.

Photo: Dr. Kurt Schnitzer, Photo Conrado, American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee Archives, New York, NY

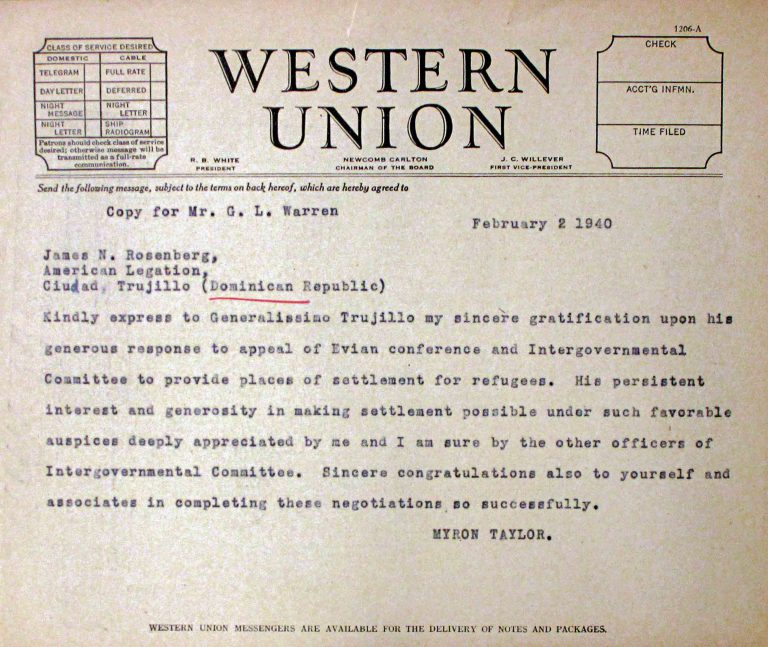

Myron C. Taylor to James Rosenberg, February 2, 1940

Through James Rosenberg, DORSA representative in the capital of the Dominican Republic, Myron C. Taylor conveys his deep appreciation to the dictator Trujillo for his generous reaction to the Évian Conference’s appeal for settlement opportunities for refugees.

Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, NY

Myron C. Taylor to James Rosenberg, February 2, 1940

Through James Rosenberg, DORSA representative in the capital of the Dominican Republic, Myron C. Taylor conveys his deep appreciation to the dictator Trujillo for his generous reaction to the Évian Conference’s appeal for settlement opportunities for refugees.

Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, NY

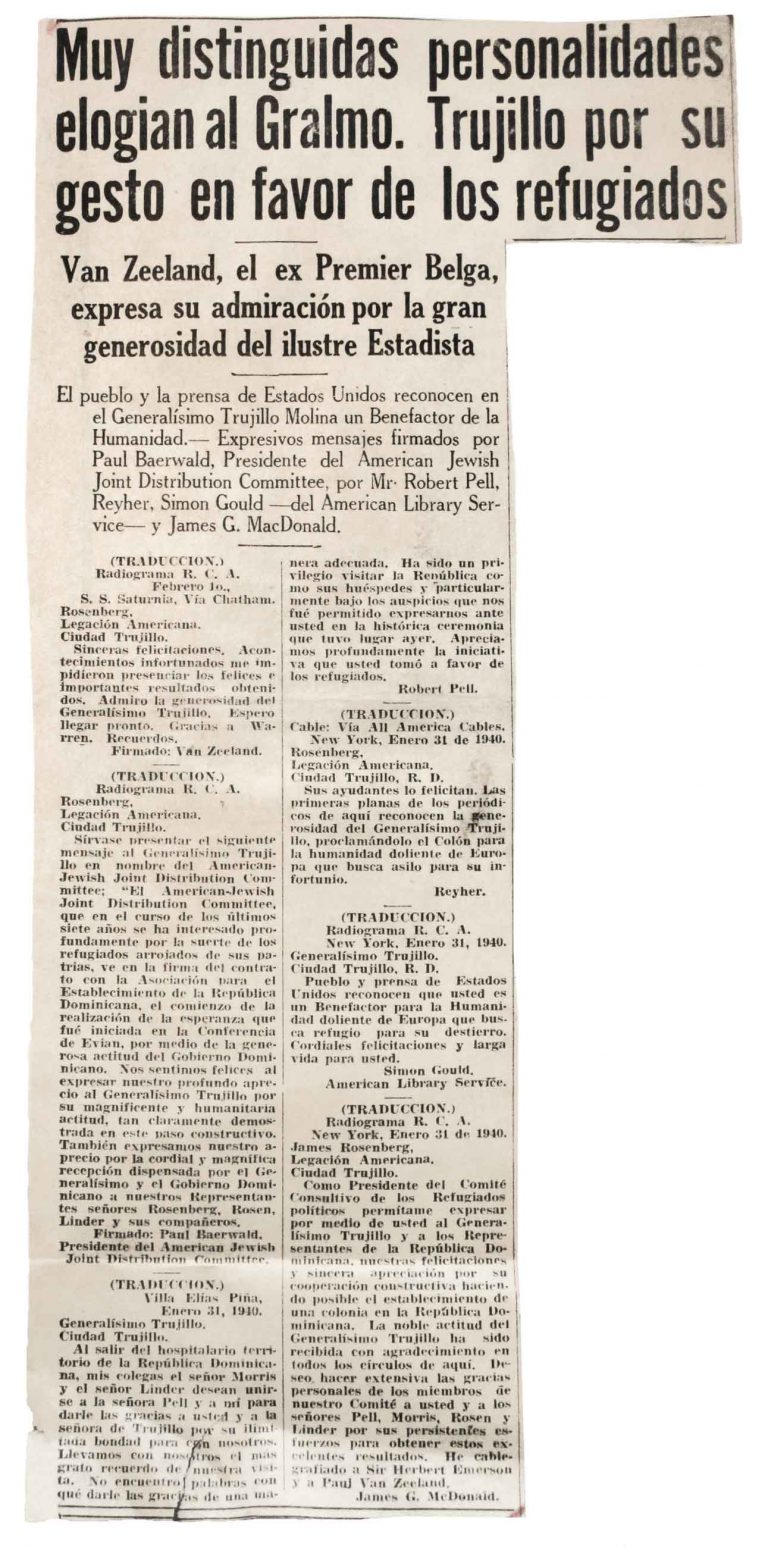

Listin Diario, Dominican Republic, February 3, 1940

The Trujillo regime uses the recognition from the outside for propaganda within the country: The Dominican press publishes telegrams sent by “eminent personalities who treasure General Trujillo for his gesture towards the refugees.”

National Archives, College Park, MD

Listin Diario, Dominican Republic, February 3, 1940

The Trujillo regime uses the recognition from the outside for propaganda within the country: The Dominican press publishes telegrams sent by “eminent personalities who treasure General Trujillo for his gesture towards the refugees.”

National Archives, College Park, MD

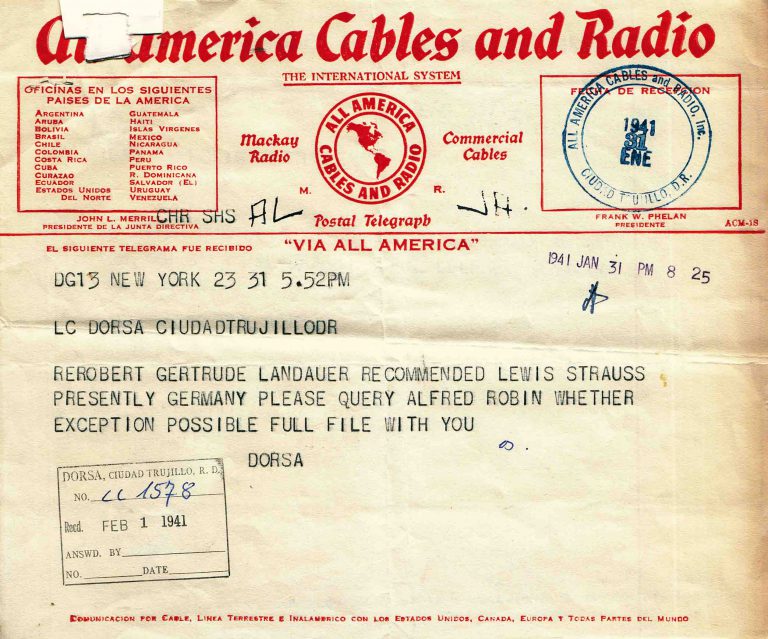

From DORSA headquarters in New York to the branch in Ciudad Trujillo (Santo Domingo), January 3, 1941

The message asks if an exception can be made for the 47-year-old businessman Robert Landauer and his wife Gertrude to admit them to Sosúa, since both are still in Germany and therefore in great danger.

National Archives, College Park, MD

From DORSA headquarters in New York to the branch in Ciudad Trujillo (Santo Domingo), January 3, 1941

The message asks if an exception can be made for the 47-year-old businessman Robert Landauer and his wife Gertrude to admit them to Sosúa, since both are still in Germany and therefore in great danger.

National Archives, College Park, MD

A Kibbutz in a Caribbean Dictatorship

Clips from Interview with Barbara Steinmetz, January 18, 1998, Saginaw, Michigan, USA

© United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, RG-50.120*0030)Interview Code 38619

and Clips from Dominican Republic Settlement Association Inc., Sosúa – Haven in the Caribbean, 1941

© National Archives at College Park, MD, DRSA-DRSA-180

A Kibbutz in a Caribbean Dictatorship

Clips from Interview with Barbara Steinmetz, January 18, 1998, Saginaw, Michigan, USA

© United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, RG-50.120*0030)Interview Code 38619

and Clips from Dominican Republic Settlement Association Inc., Sosúa – Haven in the Caribbean, 1941

© National Archives at College Park, MD, DRSA-DRSA-180