Cuba

Policy on Immigration and Refugees

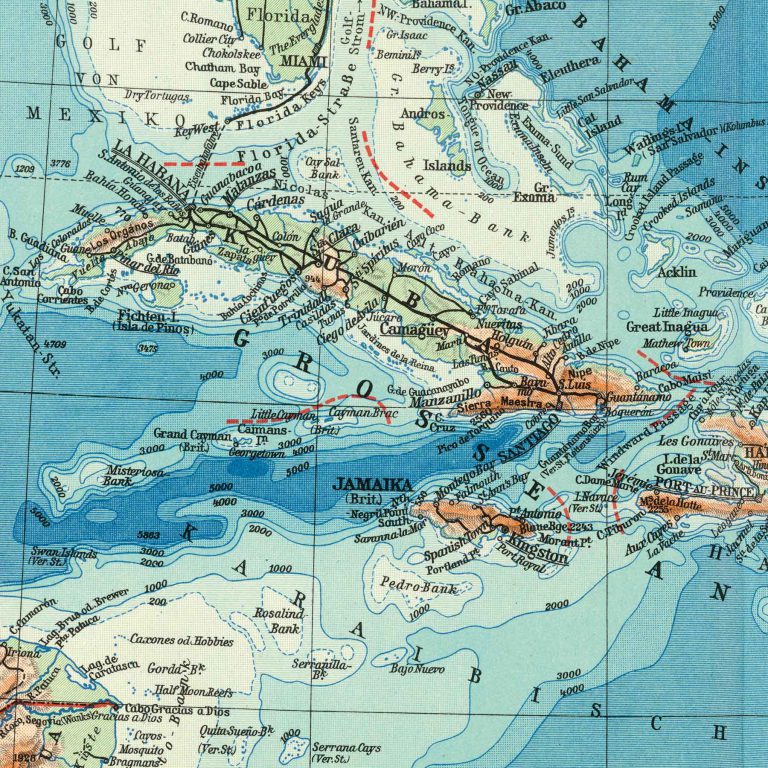

Despite numerous battles for independence, Cuba remains part of the Spanish Empire until 1898, when the United States occupies the country. Cuba formally achieves independence in 1902, but its de-facto independence remains limited due to its location within the United States’ declared sphere of influence. Immigration from the US and Europe grows; meanwhile, companies recruit workers from Jamaica, Barbados, and Haiti for the sugar industry, the cornerstone of the country’s economy – thwarting efforts to “lighten” the population.

After being granted permission to immigrate as late as 1881, Jews begin arriving from the Mediterranean region and Eastern Europe. Between 1921 and 1923, many of them stay at “Hotel Cuba” as a stopover en route to the US.

In 1925, in part thanks to American backing, General Gerardo Machado y Morales takes power and turns the country into a dictatorship during the Great Depression with the aid of the secret police and the military. In 1933, he is overthrown amidst a general strike. The new president, Ramón Grau San Martín, initiates a program of economic and social reforms. These “revolutionary” measures have a nationalistic bent; for instance, a new law specifies that at least half of any company’s workforce must be Cuban, a stipulation with a severe impact on many immigrants.

Grau, whose rule the US government refuses to recognize, only remains in power for four months. This is followed by a “dictatorship dressed up as democracy.” The new chief of the armed forces, Fulgencio Batista Zaldívar, installs several puppet presidents through 1940. In 1937, he makes a political about-face and claims to be completing the work of the major reforms of 1933, despite American resistance. The only Cuban president of the 1930s to serve out nearly his entire term is Federico Laredo Brú (1936–40). Although the Brú administration distances itself from antisemitic currents when segments of the Cuban elite are flirting with these and fascist ideas, it remains unreceptive to American appeals that Cuba should admit German Jews.

Nevertheless, thanks to liberal immigration laws, 5,000 European Jews land in Cuba before the tightening of visa requirements in early May 1939. From then on, a visa requires approval from the foreign and labor ministries as well as the immigration authorities; tourist visas are no longer granted or honored. For the nearly 1,000 refugees who have booked voyages to Cuba on the St. Louis in June 1939, this new stipulation brings immeasurable suffering.

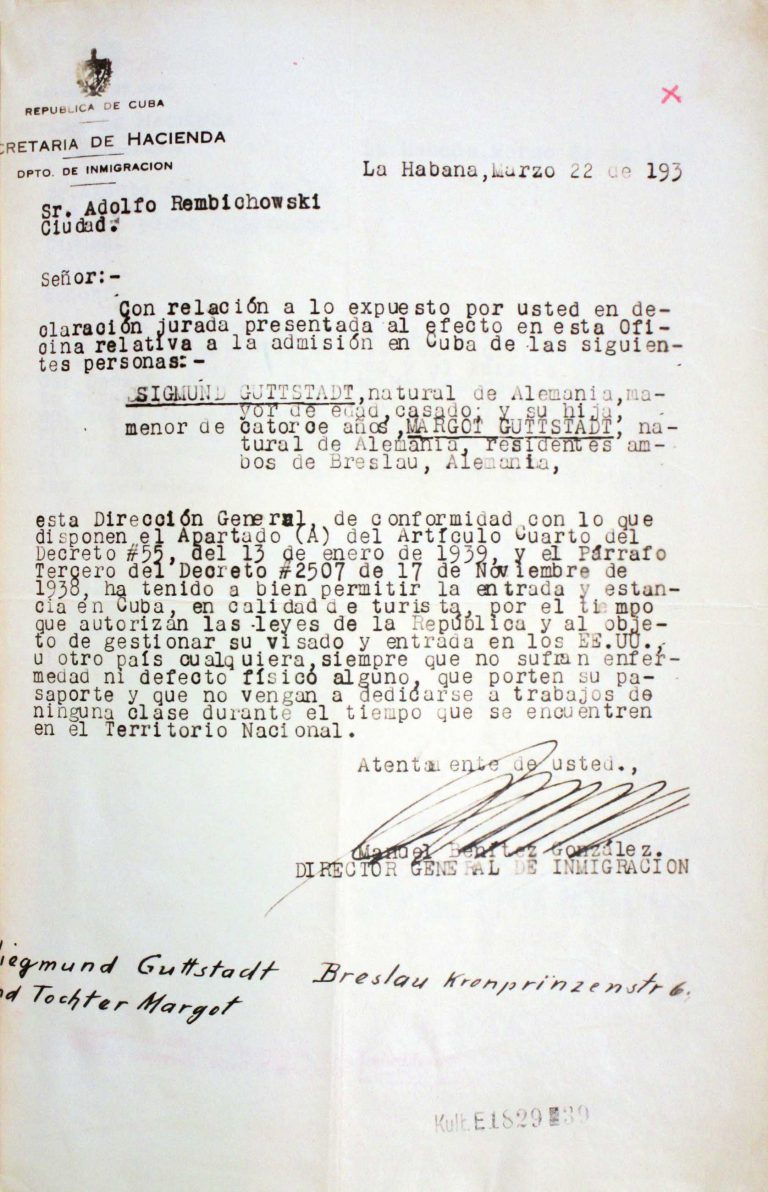

Tourist entry permit issued by Manuel Benitez González of the Cuban Immigration Authority for Siegmund Guttstadt and his daughter Margot, March 1939

One obstacle to immigration is posed by the strict labor quotas. Batista’s protégé Benitez exploits his post as director of the Immigration Authority to sell entry permits outside the scope of the regular provisions.

Auswärtiges Amt / Politisches Archiv, Berlin, R 67186

Tourist entry permit issued by Manuel Benitez González of the Cuban Immigration Authority for Siegmund Guttstadt and his daughter Margot, March 1939

One obstacle to immigration is posed by the strict labor quotas. Batista’s protégé Benitez exploits his post as director of the Immigration Authority to sell entry permits outside the scope of the regular provisions.

Auswärtiges Amt / Politisches Archiv, Berlin, R 67186

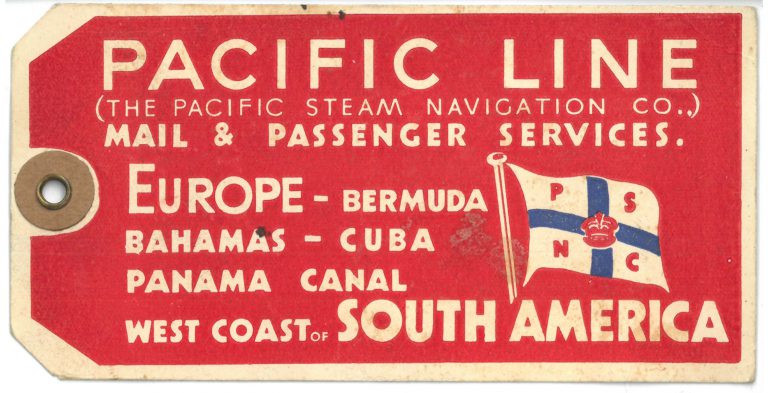

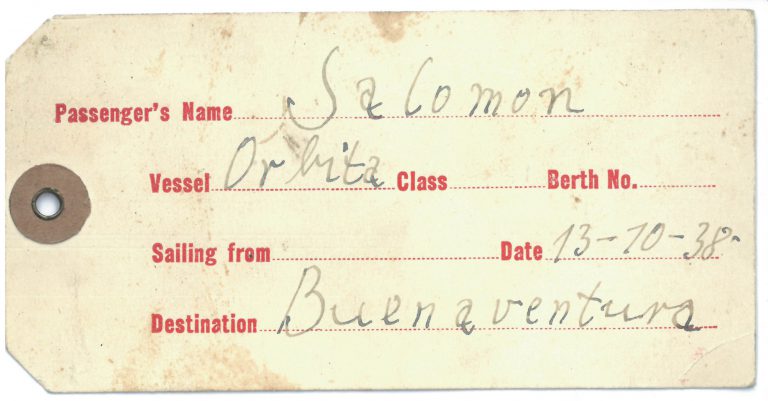

The Salomon family’s luggage tag for their voyage to Buenaventura in October 1938

“Citizens of the German Reich” do not yet require a visa. Each arriving foreigner must leave a 500 US$ deposit with the Ministry of the Interior for at least two years, payable through the shipping company. The transit visa permits a stay of up to ninety days. Tourists without a return or onward ticket must deposit a landing fee of 300 US$.

Sammlung Wolfgang Haney, Berlin

The Salomon family’s luggage tag for their voyage to Buenaventura in October 1938

“Citizens of the German Reich” do not yet require a visa. Each arriving foreigner must leave a 500 US$ deposit with the Ministry of the Interior for at least two years, payable through the shipping company. The transit visa permits a stay of up to ninety days. Tourists without a return or onward ticket must deposit a landing fee of 300 US$.

Sammlung Wolfgang Haney, Berlin

The Salomon family’s luggage tag for their voyage to Buenaventura in October 1938

“Citizens of the German Reich” do not yet require a visa. Each arriving foreigner must leave a 500 US$ deposit with the Ministry of the Interior for at least two years, payable through the shipping company. The transit visa permits a stay of up to ninety days. Tourists without a return or onward ticket must deposit a landing fee of 300 US$.

Sammlung Wolfgang Haney, Berlin

The Salomon family’s luggage tag for their voyage to Buenaventura in October 1938

“Citizens of the German Reich” do not yet require a visa. Each arriving foreigner must leave a 500 US$ deposit with the Ministry of the Interior for at least two years, payable through the shipping company. The transit visa permits a stay of up to ninety days. Tourists without a return or onward ticket must deposit a landing fee of 300 US$.

Sammlung Wolfgang Haney, Berlin

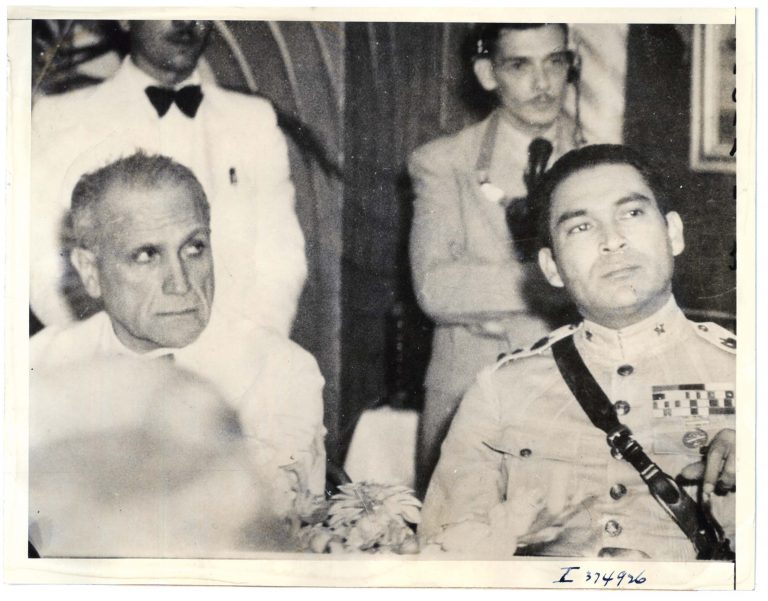

President Laredo Brú (left) and Batista (right), chief of the armed forces, December 1936

Batista is the “strongman” pulling the strings in Cuba. In 1940, he arranges to be elected head of state. His popularity comes at the old elites’ expense, for Batista has been the target of discrimination by the white upper classes. After changing course in 1937, he strengthens unions, legalizes the Communist Party, and redistributes state-owned land.

Zentrum für Antisemitismusforschung / Technische Universtät Berlin

President Laredo Brú (left) and Batista (right), chief of the armed forces, December 1936

Batista is the “strongman” pulling the strings in Cuba. In 1940, he arranges to be elected head of state. His popularity comes at the old elites’ expense, for Batista has been the target of discrimination by the white upper classes. After changing course in 1937, he strengthens unions, legalizes the Communist Party, and redistributes state-owned land.

Zentrum für Antisemitismusforschung / Technische Universtät Berlin

Delegation

Juan Antiga y Escobar

* 23 August 1871 Mayajigua † 9 February 1939 Havanna

Raised in an impoverished family, Juan Antiga y Escobar studies medicine on a scholarship for gifted students. He leaves the Spanish colony of Cuba to finish his training and works in many countries of North and South America.

In Mexico, Antiga y Escobar becomes a well-known homeopathy specialist across Latin America. He advocates for Cuban independence and returns there in 1911. In the 1920s, he is a member of the Grupo Minoristas, a league of intellectuals, doctors, social scientists, and artists who oppose the Cuban dictatorship and appeal for modernizing the society.

In 1934, Antiga y Escobar becomes the director of a new agency for labor and social reform, whose establishment he had advocated in 1913 in his second dissertation, this time in law. He serves as a Cuban envoy and diplomatic representative in Switzerland and France and as a permanent delegate to the League of Nations.

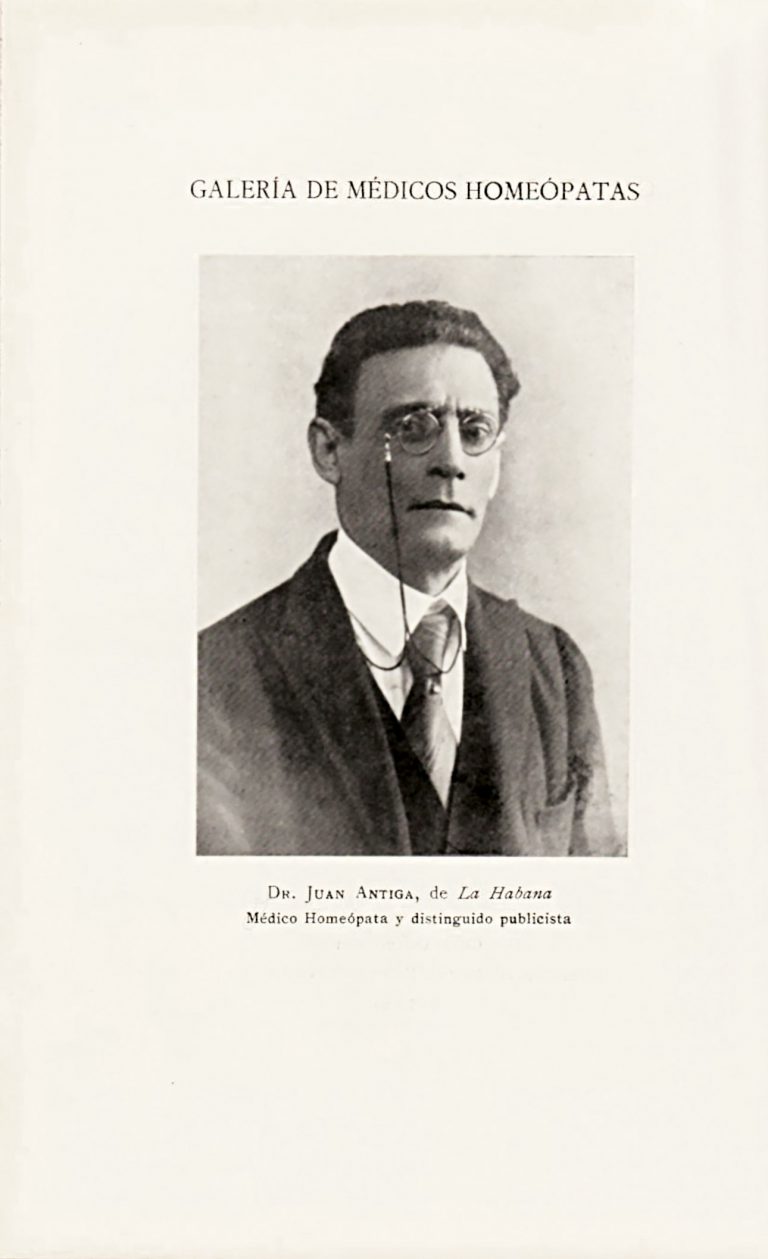

Juan Antiga y Escobar, undated

Antiga y Escobar makes a name for himself as a homeopathy specialist. In 1927, he argues that social and medical problems are connected and calls for better working conditions. His call for modernizing society accompanies his criticism of the negative impacts of modern market and production mechanisms.

El Sol de Meissen 1933, Liga-Hispano-Americana Pro-Homeopatía

Juan Antiga y Escobar, undated

Antiga y Escobar makes a name for himself as a homeopathy specialist. In 1927, he argues that social and medical problems are connected and calls for better working conditions. His call for modernizing society accompanies his criticism of the negative impacts of modern market and production mechanisms.

El Sol de Meissen 1933, Liga-Hispano-Americana Pro-Homeopatía

Conference Contributions

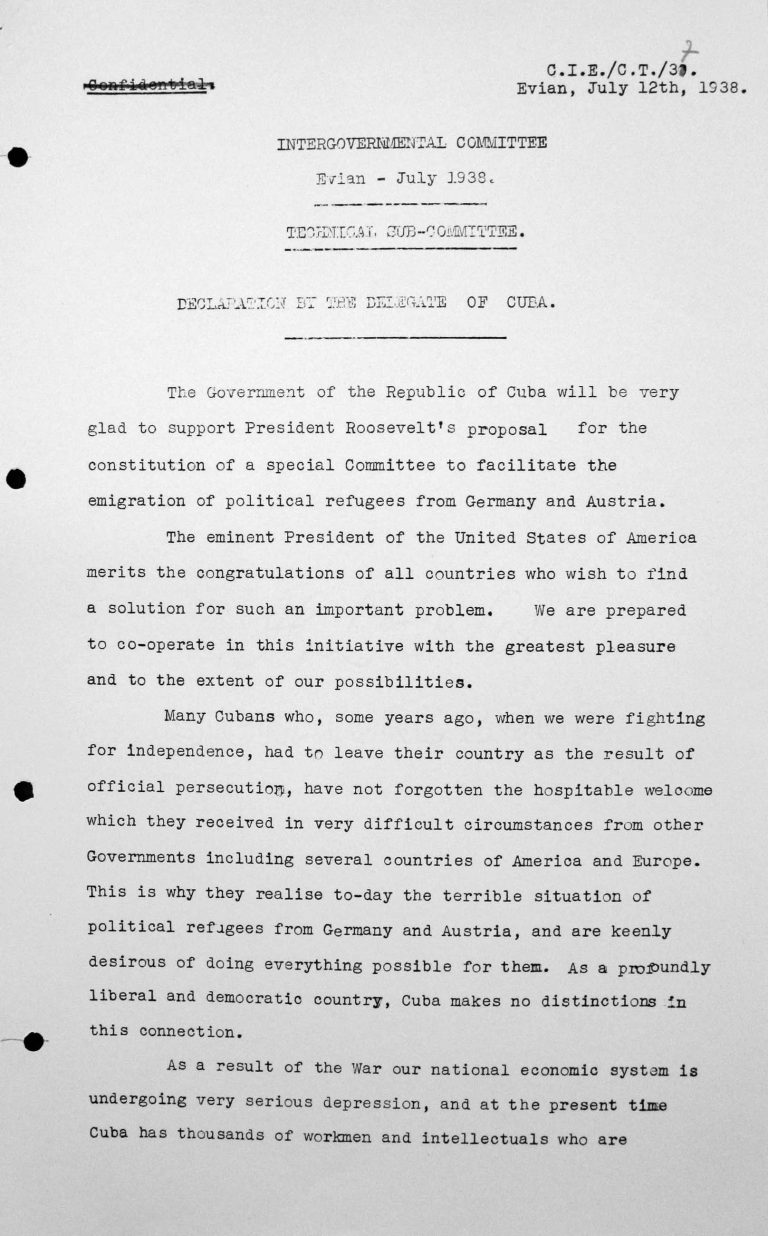

Declaration by the delegate of Cuba for the Technical Sub-Committee, July 12, 1938, p. 1/3

Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, NY

Declaration by the delegate of Cuba for the Technical Sub-Committee, July 12, 1938, p. 1/3

Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, NY

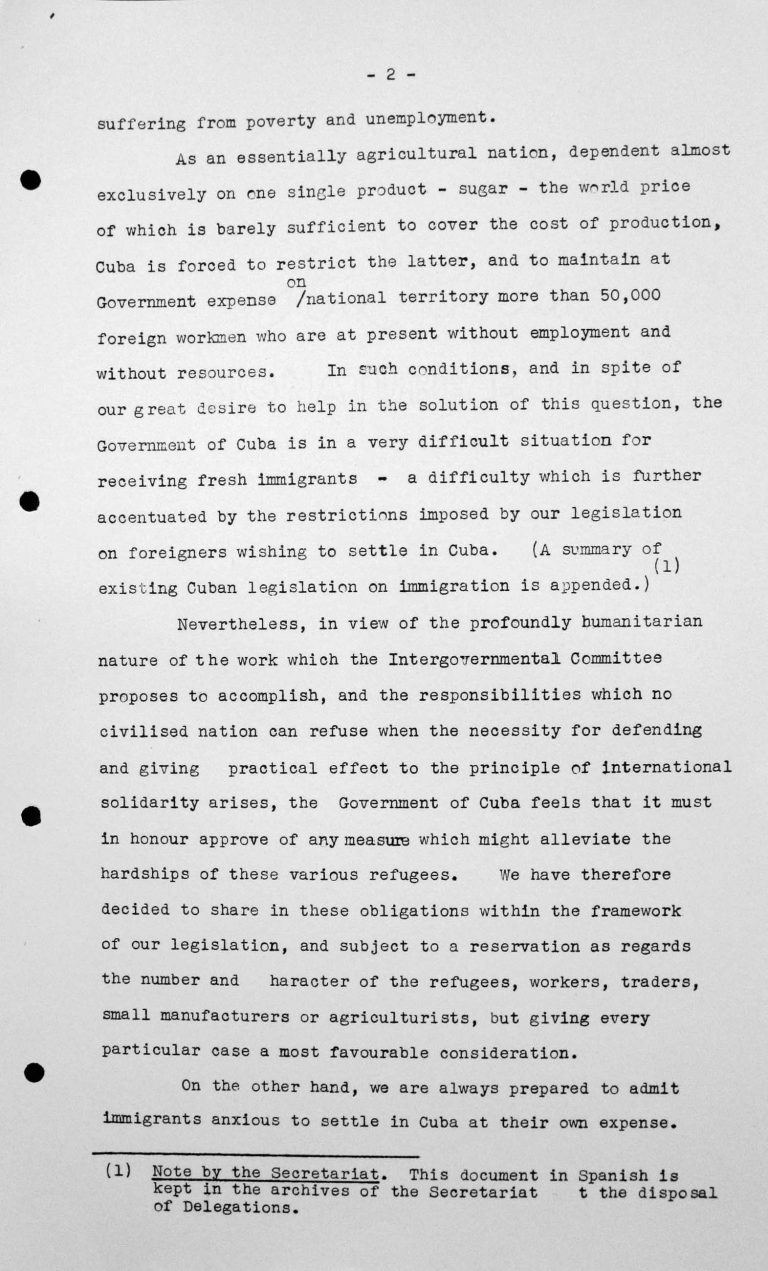

Declaration by the delegate of Cuba for the Technical Sub-Committee, July 12, 1938, p. 2/3

Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, NY

Declaration by the delegate of Cuba for the Technical Sub-Committee, July 12, 1938, p. 2/3

Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, NY

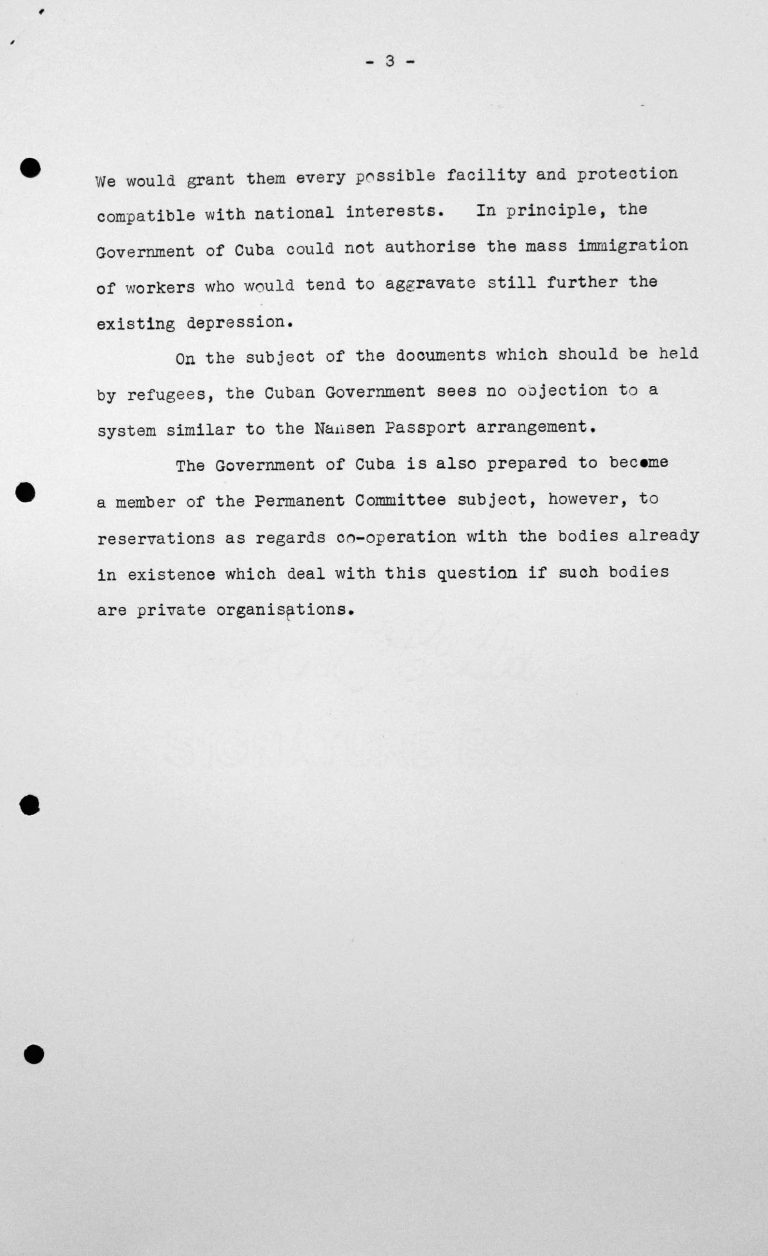

Declaration by the delegate of Cuba for the Technical Sub-Committee, July 12, 1938, p. 3/3

Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, NY

Declaration by the delegate of Cuba for the Technical Sub-Committee, July 12, 1938, p. 3/3

Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, NY