Chile

Policy on Immigration and Refugees

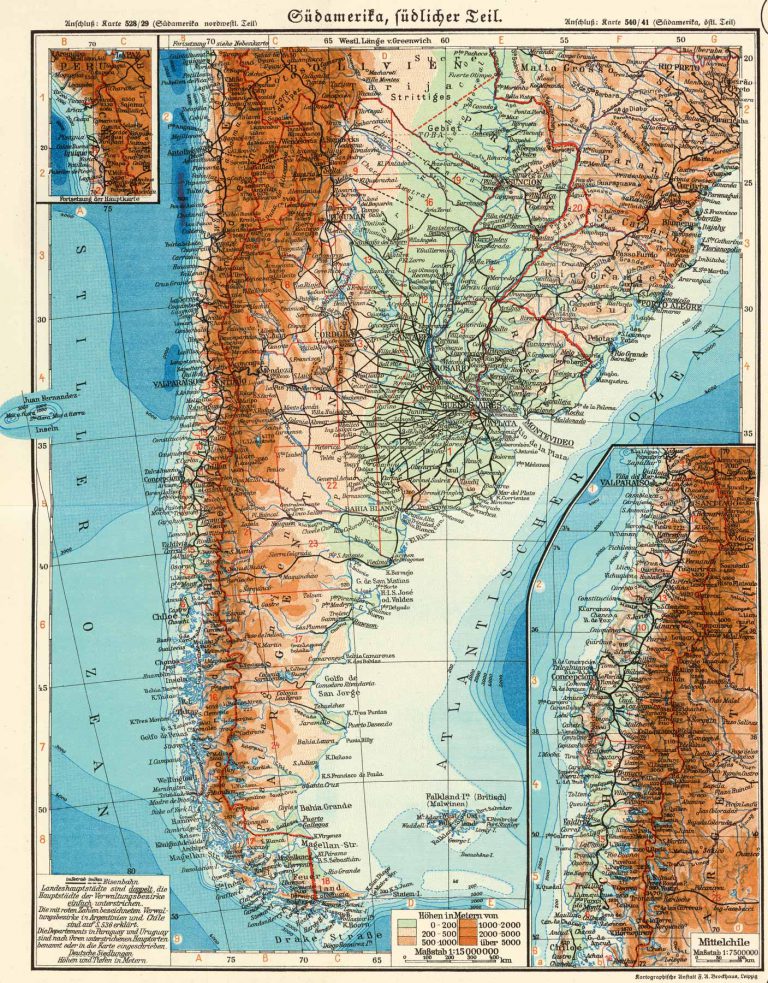

The immigration policy of Chile, which has been independent since 1818, is mainly focused on expanding the country’s agricultural borders and on colonization, at the expense of the indigenous population. In the 19th century, German-speaking immigrants and others enter the country, while in the 20th century, Jews from Russia and the Balkans are among the country’s immigrants, although viewed as “racially undesirable.”

After 1929, export earnings for Chile’s largest industries, saltpeter and copper, collapse and unemployment rises. In 1931 the dictatorial regime of President Carlos Ibáñez del Campo is overthrown; the ensuing political chaos ends only in 1932 with the election of Arturo Alessandri Palma, who previously served as president from 1920 to 1925 as a member of the Liberal Alliance. In his second term, however, he governs as a conservative, tightening immigration policy to protect the domestic labor market. Now it is mainly farmers who are let in, and quotas are placed on Jewish immigration.

Despite increasing restrictions, several hundred German Jews enter Chile during the first years of the National Socialist regime. Simultaneously, fascist and nationalistic movements strengthen in Chile. The Movimiento Nacionalsocialista de Chile, founded in 1932, is supported by the German Embassy and the Nazi Party’s international organization.

However, the increasing nationalism and rightward shift do not remain unchallenged: In 1936 Jewish immigrants establish the Comité Contra el Antisemitismo, while Communists, Socialists and radicals join together to form the Frente Popular (Popular Front), which takes power at the end of 1938.

The new president, Pedro Aguirre Cerda, supports a liberal immigration policy, especially towards republican refugees from Spain. A special office of the Foreign Ministry is set up to admit 3,000 Jews from Germany and Austria. As the result of this new, liberal policy, the numbers of new immigrants skyrocket. The extreme right then attacks the government for endangering national security. The debate in the parliament and press is tinged by overt antisemitism.

After being accused of enriching himself through awarding “Jewish visas,” the foreign minister is forced to resign in 1940 and the humanitarian admission process ends because of pressure from immigration opponents and the delaying and denial of visas by right-wing consuls. Nevertheless, Chile remains one of the most important Latin American destinations for Jewish refugees.

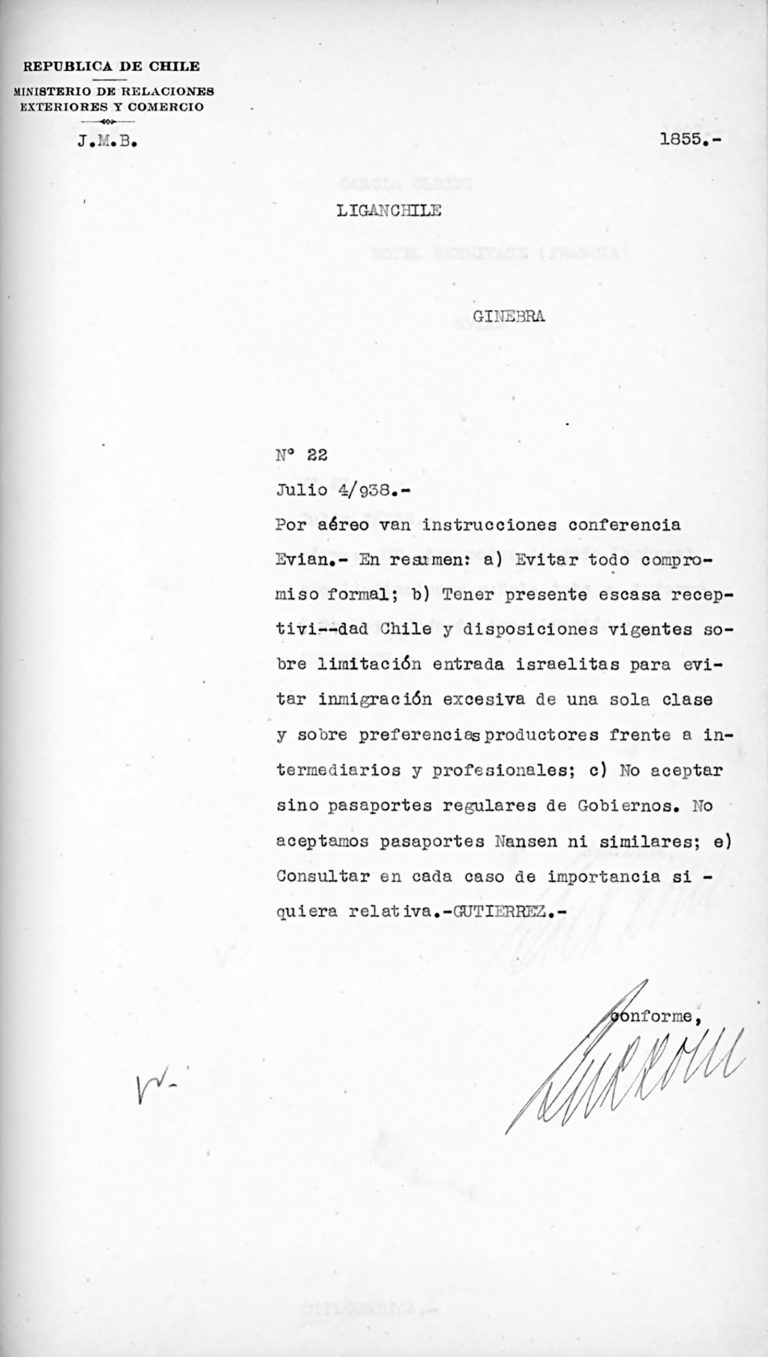

“Instructions” of the Chilean foreign minister José Ramón Gutiérrez Allende for the delegation in Évian, July 4, 1938

Little attention is given to the Évian Conference in Chile, since immigration under Alessandri is considered regulated. The restrictive provisions are also reflected in the instructions: “Avoid any formal compromise … Take into consideration existing laws limiting access for Jews, in order to avoid excessive immigration of a specific group.”

Archivo General Histórico, Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores de Chile, Santiago de Chile

“Instructions” of the Chilean foreign minister José Ramón Gutiérrez Allende for the delegation in Évian, July 4, 1938

Little attention is given to the Évian Conference in Chile, since immigration under Alessandri is considered regulated. The restrictive provisions are also reflected in the instructions: “Avoid any formal compromise … Take into consideration existing laws limiting access for Jews, in order to avoid excessive immigration of a specific group.”

Archivo General Histórico, Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores de Chile, Santiago de Chile

Jewish refugees from Austria on the SS Virgilio on a crossing from Italy to Chile, July 1939

At least 13,000 Jews reach Chile between 1933 and 1945. Most settle in the capital city of Santiago and are supported by relief organizations and the Jewish community. Many are able to build a new life in Chile.

Photo: Leo Spitzer / United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington

Jewish refugees from Austria on the SS Virgilio on a crossing from Italy to Chile, July 1939

At least 13,000 Jews reach Chile between 1933 and 1945. Most settle in the capital city of Santiago and are supported by relief organizations and the Jewish community. Many are able to build a new life in Chile.

Photo: Leo Spitzer / United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington

Pablo Neruda, 1950

Pablo Neruda is among a group of Chilean intellectuals who strongly condemn the Nazis’ persecution of the Jews. On November 20, 1938 the Alianza de Intelectuales de Chile, of which he is the founder, organizes a rally that is attended by 10,000 people. Their advocacy of the admission of Jewish refugees demonstrates that antisemitism is not completely dominant in Chile.

Archivo General Histórico, Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores de Chile, Santiago de Chile / Wikimedia Commons

Pablo Neruda, 1950

Pablo Neruda is among a group of Chilean intellectuals who strongly condemn the Nazis’ persecution of the Jews. On November 20, 1938 the Alianza de Intelectuales de Chile, of which he is the founder, organizes a rally that is attended by 10,000 people. Their advocacy of the admission of Jewish refugees demonstrates that antisemitism is not completely dominant in Chile.

Archivo General Histórico, Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores de Chile, Santiago de Chile / Wikimedia Commons

Delegation

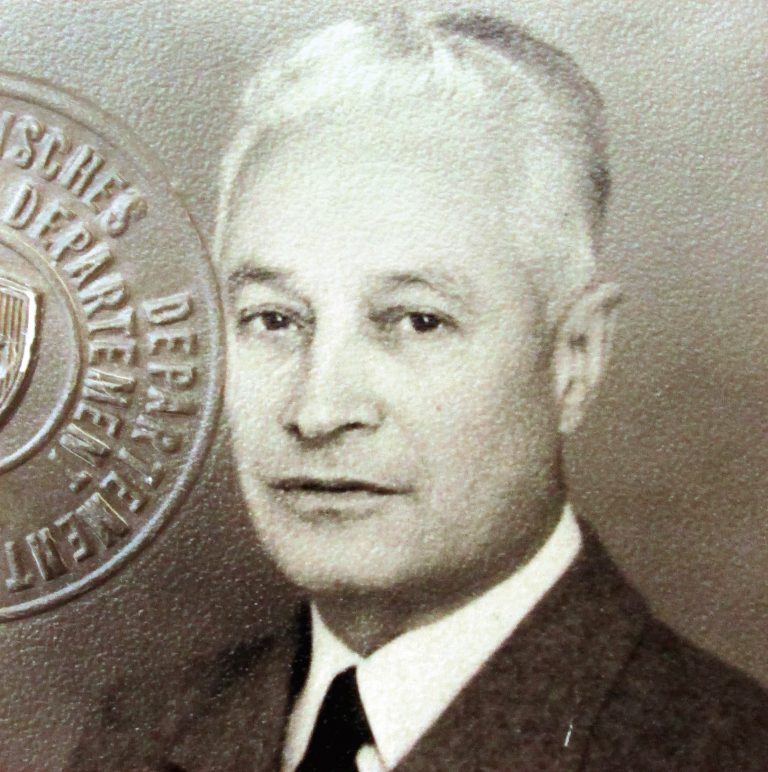

Fernando Garcia Oldini

* 1896 or 1898 † 13 May 1965 Genf

Fernando Garcia Oldini works as a writer and, beginning in 1924, as the editor of the Chilean daily newspaper La Nacion. He also begins a diplomatic career. After studying economics in Geneva, he works at the International Labor Organization of the League of Nations, focusing on social welfare; he is a delegate there until at least the 1950s. Beginning in 1927, he serves as honorary consul in Bern, from which he returns to Chile in 1932 in order to take over the position of labor and health minister in the cabinet of Arturo Alessandri, a job he holds until 1934.

In the following years he represents Chile as envoy in Switzerland, Austria, Hungary and Spain and also as permanent delegate at the League of Nations. In 1948 he again returns to his country as head of the diplomatic department of the Chilean Foreign Ministry; in the early 1950s, he serves briefly as foreign minister. In 1953 Garcia Oldini again receives the post of envoy in Switzerland and becomes ambassador there in 1957.

Fernando Garcia Oldini in the 1950s as envoy in Bern

Schweizerisches Bundesarchiv, Bern, E2001E#197884#2275

Fernando Garcia Oldini in the 1950s as envoy in Bern

Schweizerisches Bundesarchiv, Bern, E2001E#197884#2275

Conference Contributions

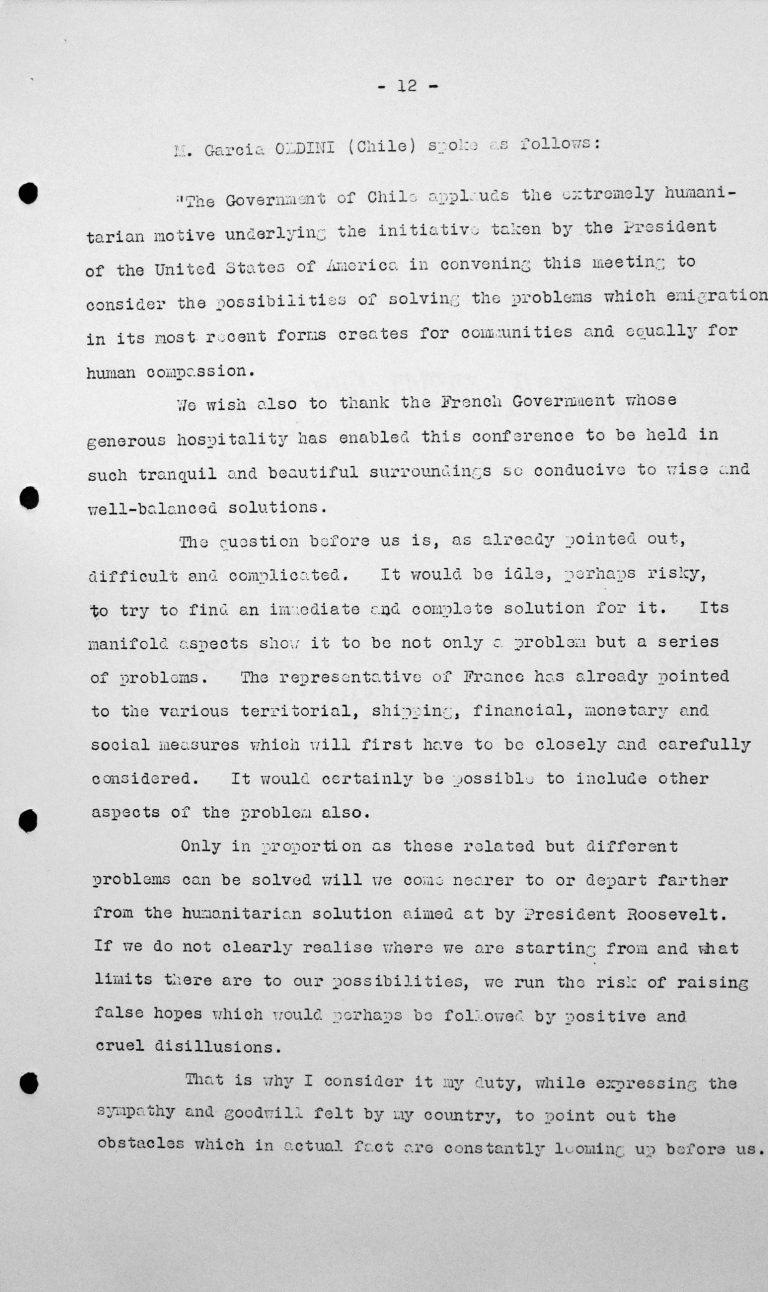

Speech by Fernando Garcia Oldini (Chili) in the public session on July 9, 1938, 11am, p. 1/3

Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, NY

Speech by Fernando Garcia Oldini (Chili) in the public session on July 9, 1938, 11am, p. 1/3

Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, NY

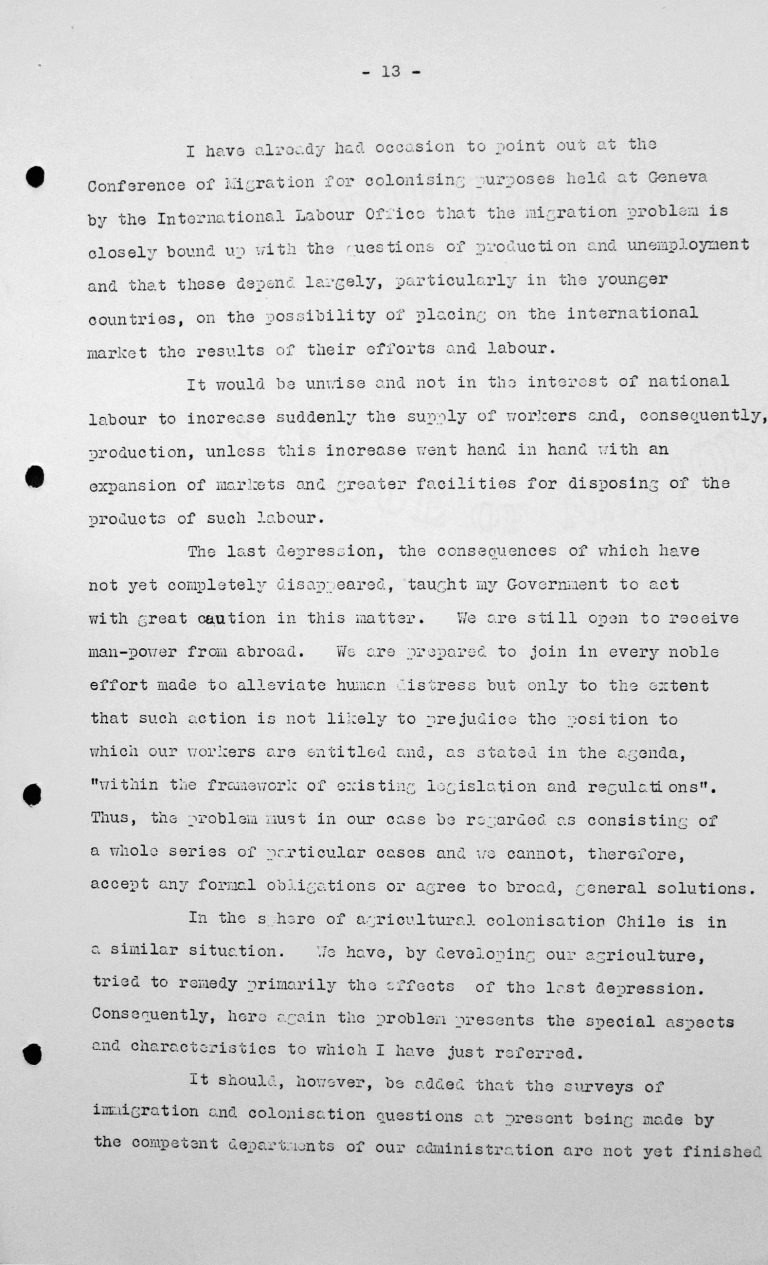

Speech by Fernando Garcia Oldini (Chili) in the public session on July 9, 1938, 11am, p. 2/3

Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, NY

Speech by Fernando Garcia Oldini (Chili) in the public session on July 9, 1938, 11am, p. 2/3

Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, NY

Speech by Fernando Garcia Oldini (Chili) in the public session on July 9, 1938, 11am, p. 3/3

Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, NY

Speech by Fernando Garcia Oldini (Chili) in the public session on July 9, 1938, 11am, p. 3/3

Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, NY

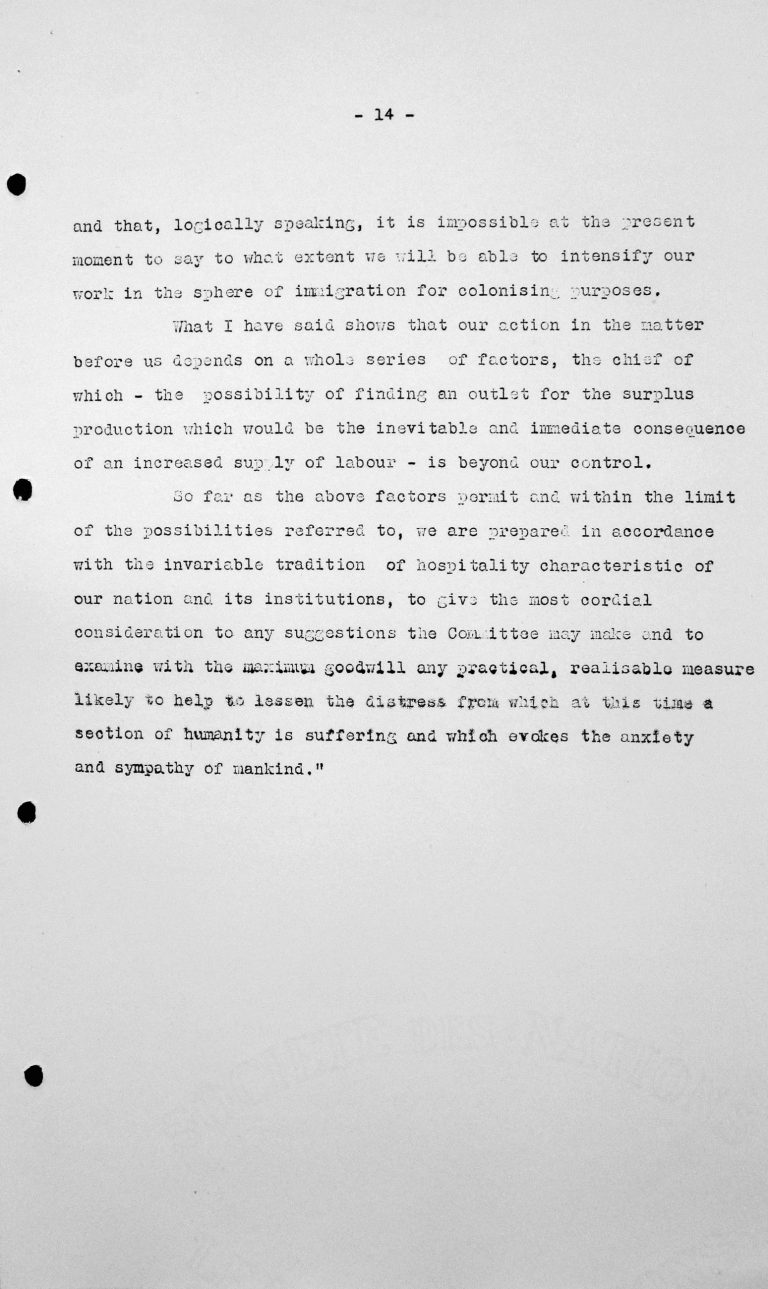

Declaration by the delegation of Chili to the Technical Sub-Committee regarding identity papers, July 12, 1938

Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, NY

Declaration by the delegation of Chili to the Technical Sub-Committee regarding identity papers, July 12, 1938

Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, NY

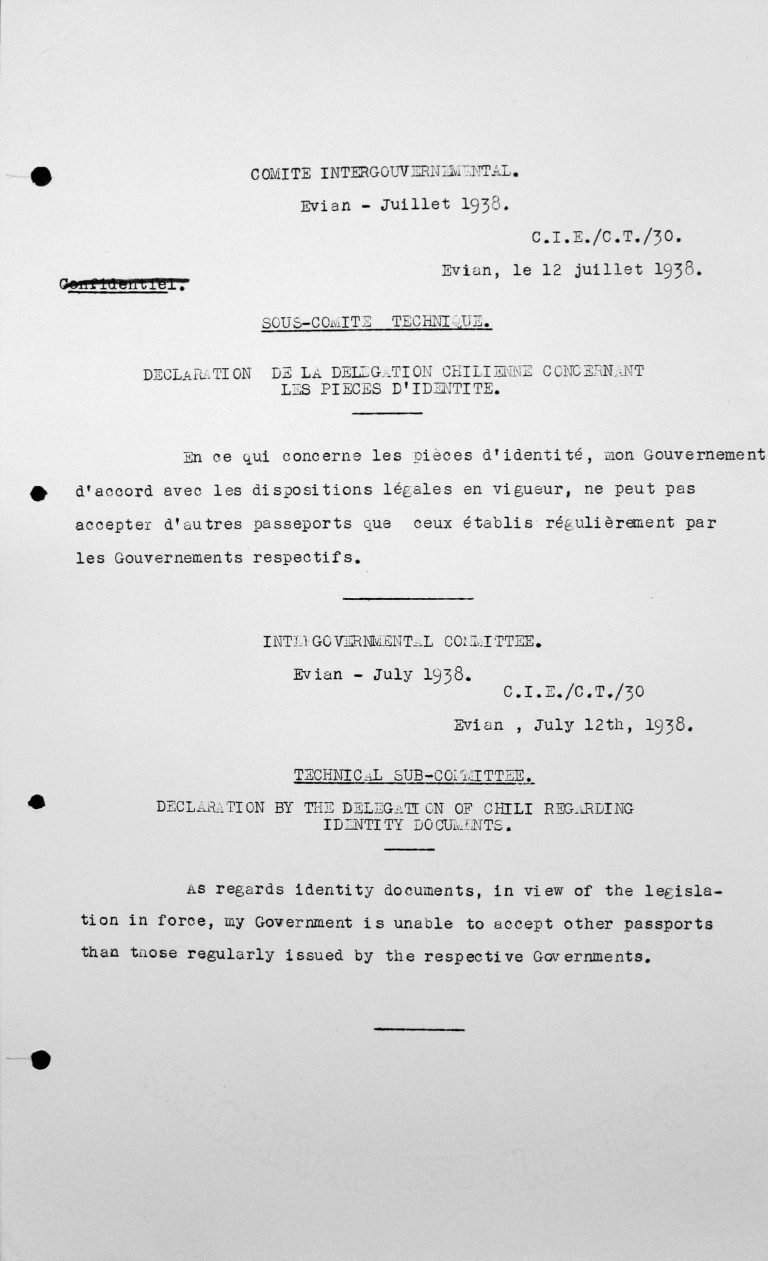

Declaration by Fernando Garcia Oldini (Chili) in the non-public session on July 14, 1938, 5pm

Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, NY

Declaration by Fernando Garcia Oldini (Chili) in the non-public session on July 14, 1938, 5pm

Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, NY