Brazil

Policy on Immigration and Refugees

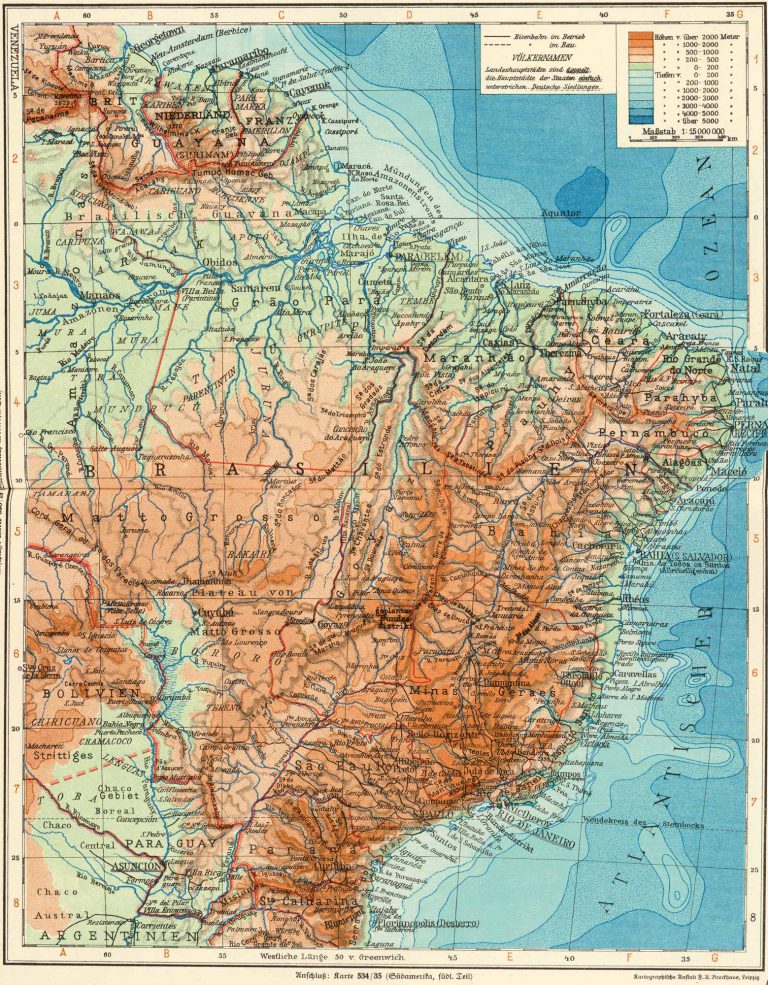

The majority of Brazil’s population in the 19th century is descended from immigrants and people brought there forcibly from Africa, Europe or Asia. After the end of slavery in 1888, the republic promotes immigration through liberal laws in order to settle and cultivate the country’s vast land area and to meet the need for labor in the booming coffee farming business as well as in Brazil’s growing cities. However, the government seeks to prevent immigration from Africa and Asia while welcoming immigrants from Europe with open arms. In the 1920s, leading politicians and the media – influenced by eugenic ideas – call for immigration to be limited to “pure” Europeans.

Benefitting from falling coffee prices as a result of the global economic crisis, Getúlio Vargas wins the 1930 presidential election with a nationalist program focused on economic progress. His vision of an “Estado Novo” (New State) is racist, anti-communist, and antisemitic, and is based on a change in demographic policy: From now on, at least two thirds of every company’s workforce must be Brazilian.

Vargas also opposes separatist tendencies in the population, including among the German minority. New immigrants are supposed to fit in seamlessly with a “brasilidade” that is to be as white as possible, and are supposed to give up all of the characteristics of their countries of origin; with the new constitution of 1934 comes an annual immigration quota. In August 1938, President Vargas affirms his policy: “Immigrants must prove themselves as a force for progress … however, we must protect ourselves from infiltration by elements that could turn into ideological or racial deviants.”

Antisemitic forces now push forward a total ban on immigration by Jews. Visa issuance is also dependent on the attitude of the individual consulate. Beginning in 1939, there is a recommendation to issue visas to Jews who are considered “helpful” for the country’s development. The Justice Ministry, the General Staff and the political police take part in decisions about visa applications. Through this, the question of refuge for Jews becomes a national security issue. Many Jews are able to get into Brazil by giving false information about their religion. From 1933 to 1945, 23,572 Jews find refuge in Brazil.

C.V.-Zeitung. Allgemeine Zeitung des Judentums, September 15, 1938

“Emigration to Brazil.” A special report for the newspaper of the Central-Verein deutscher Staatsbürger jüdischen Glaubens (Central Association for German Citizens of the Jewish Faith) explains the new quota rules for emigration to Brazil. The number of immigrants is not supposed to exceed two percent of the number of immigrants from each country who are already settled in Brazil. The requirements that must be met in order to receive a visa, which the article names, are stringent.

Universitätsbibliothek Johann Christian Senckenberg, Frankfurt am Main

C.V.-Zeitung. Allgemeine Zeitung des Judentums, September 15, 1938

“Emigration to Brazil.” A special report for the newspaper of the Central-Verein deutscher Staatsbürger jüdischen Glaubens (Central Association for German Citizens of the Jewish Faith) explains the new quota rules for emigration to Brazil. The number of immigrants is not supposed to exceed two percent of the number of immigrants from each country who are already settled in Brazil. The requirements that must be met in order to receive a visa, which the article names, are stringent.

Universitätsbibliothek Johann Christian Senckenberg, Frankfurt am Main

US President Roosevelt (center) with Brazilian President Getúlio Vargas (left) at a meeting on a US destroyer off the Brazilian port city of Natal, January 1943

Vargas strives for closer ties to the US. At the same time, he is said to be personally sympathetic to Hitler. He adopts a policy of neutrality and balance between the power blocs, as he does not want to endanger either business with the German Reich or relations with the US.

United States Office of War Information / Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-DIG-ds-00602

US President Roosevelt (center) with Brazilian President Getúlio Vargas (left) at a meeting on a US destroyer off the Brazilian port city of Natal, January 1943

Vargas strives for closer ties to the US. At the same time, he is said to be personally sympathetic to Hitler. He adopts a policy of neutrality and balance between the power blocs, as he does not want to endanger either business with the German Reich or relations with the US.

United States Office of War Information / Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-DIG-ds-00602

Delegation

Hélio Lobo

* 27 October 1883 Juiz de Fora † 1 January 1960 Rio de Janeiro

After graduating from law school, Hélio Lobo specializes in military criminal law. He then works as an editor of various newspapers before entering the diplomatic corps. He is considered to represent a politics of Americanization that particularly seeks closer ties with the US.

As a member of the Brazilian Historic and Geographic Institute, he publishes historical studies of Brazilian diplomacy in which he argues that international law contributes to maintaining peace. His diplomatic career leads him to the peace negotiations in Versailles in 1919 as a Brazilian delegate and to London and New York from 1920 to 1926 as a consul general. In the 1920s and 1930s he also represents Brazil at the most important inter-American and international conferences.

Lobo heads the Brazilian delegation in Évian and later becomes a member of the board of the Intergovernmental Committee for Refugees in London.

Hélio Lobo, with wife and child, undated

Bain News Service / Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-DIG-ggbain-34810

Hélio Lobo, with wife and child, undated

Bain News Service / Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-DIG-ggbain-34810

Jorge Olinto de Oliveira

* 1885 Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul † unknown

The country’s second delegate is born in Porto Alegre in southern Brazil, the son of a well-known pediatrician. After completing his studies, Olinto de Oliveira pursues a diplomatic career, serving as a chargé d’affaires at the embassy in Copenhagen from 1934 to 1936 and as the first secretary and then consul general in Geneva in 1938.

After the end of World War II, he serves as Brazilian ambassador to Honduras for two years. In 1959, he returns to Europe as Brazil’s representative in Finland.

Jorge Olinto de Oliveira, ca. 1938 in Switzerland

Schweizerisches Bundesarchiv, Bern, E8150A#196763#1541

Jorge Olinto de Oliveira, ca. 1938 in Switzerland

Schweizerisches Bundesarchiv, Bern, E8150A#196763#1541

Conference Contributions

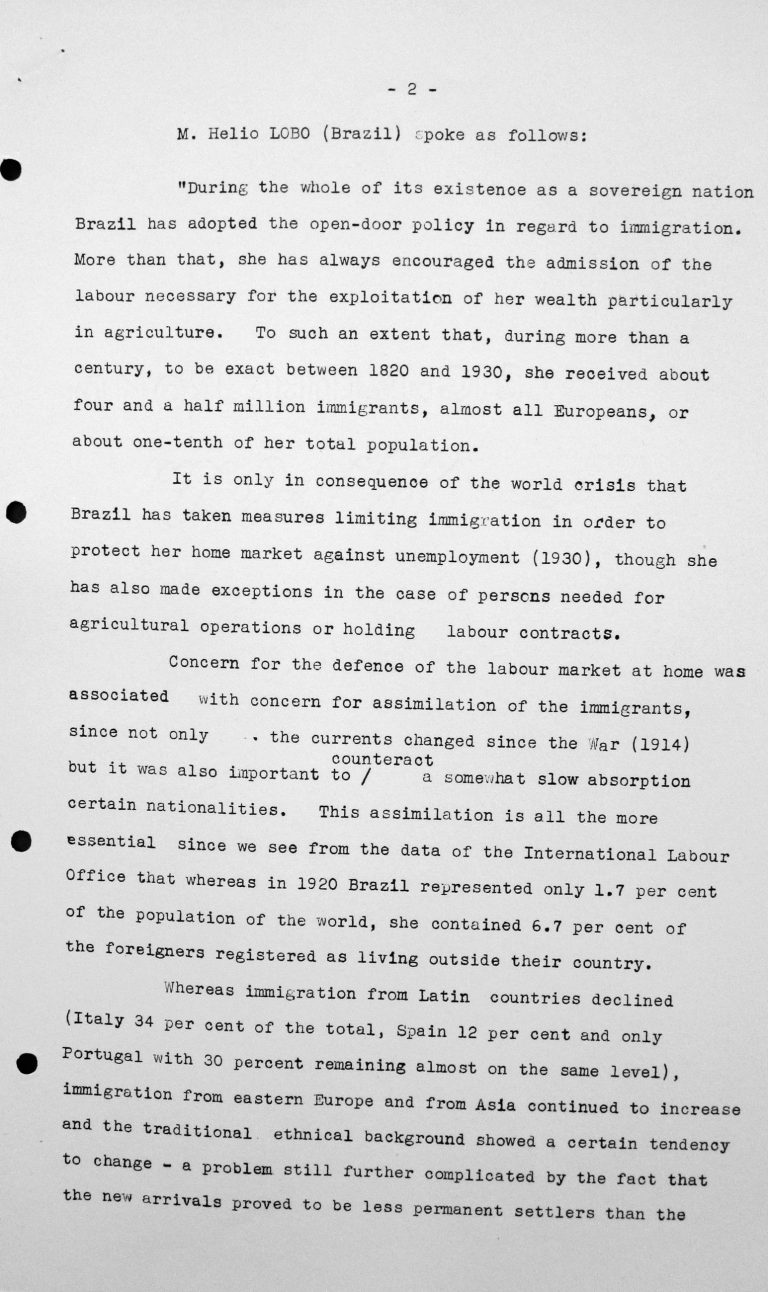

Speech by Hélio Lobo (Brazil) in the public session on July 7, 1938, 3.30pm, p. 1/3

Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, NY

Speech by Hélio Lobo (Brazil) in the public session on July 7, 1938, 3.30pm, p. 1/3

Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, NY

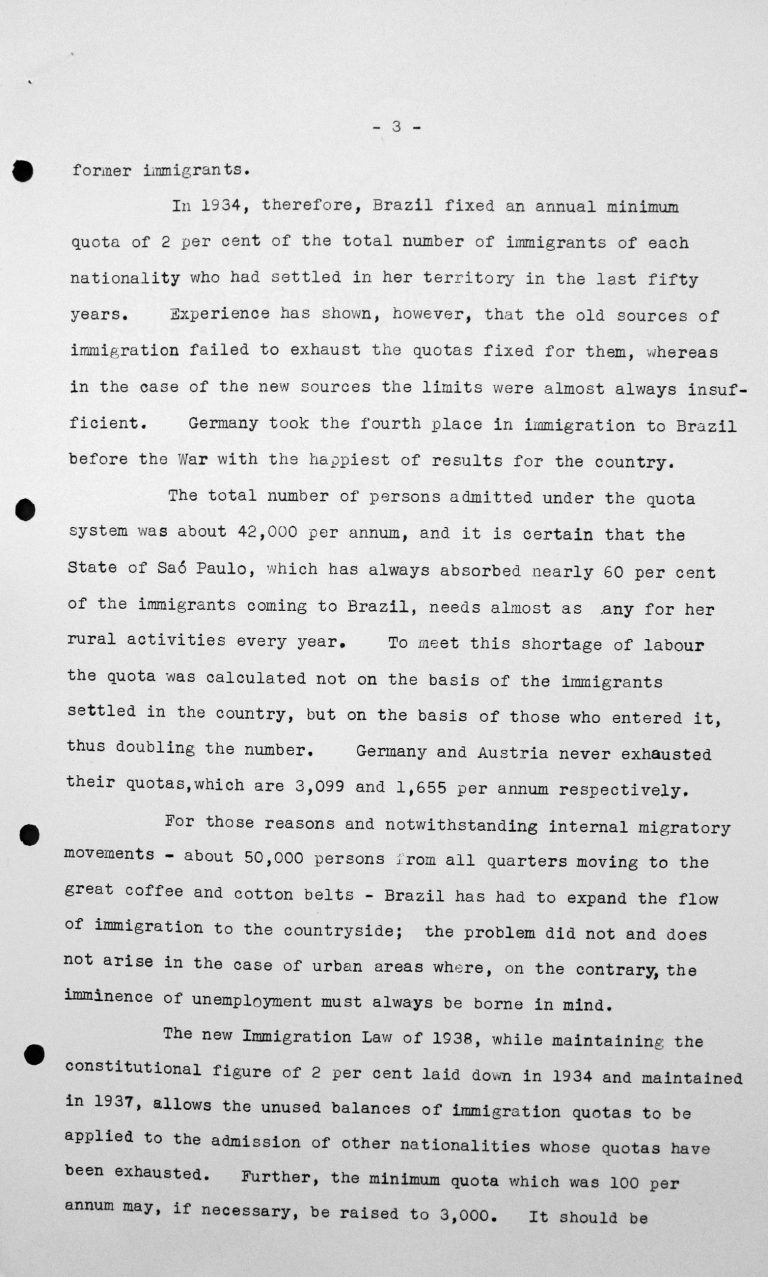

Speech by Hélio Lobo (Brazil) in the public session on July 7, 1938, 3.30pm, p. 2/3

Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, NY

Speech by Hélio Lobo (Brazil) in the public session on July 7, 1938, 3.30pm, p. 2/3

Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, NY

Speech by Hélio Lobo (Brazil) in the public session on July 7, 1938, 3.30pm, p. 3/3

Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, NY

Speech by Hélio Lobo (Brazil) in the public session on July 7, 1938, 3.30pm, p. 3/3

Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, NY

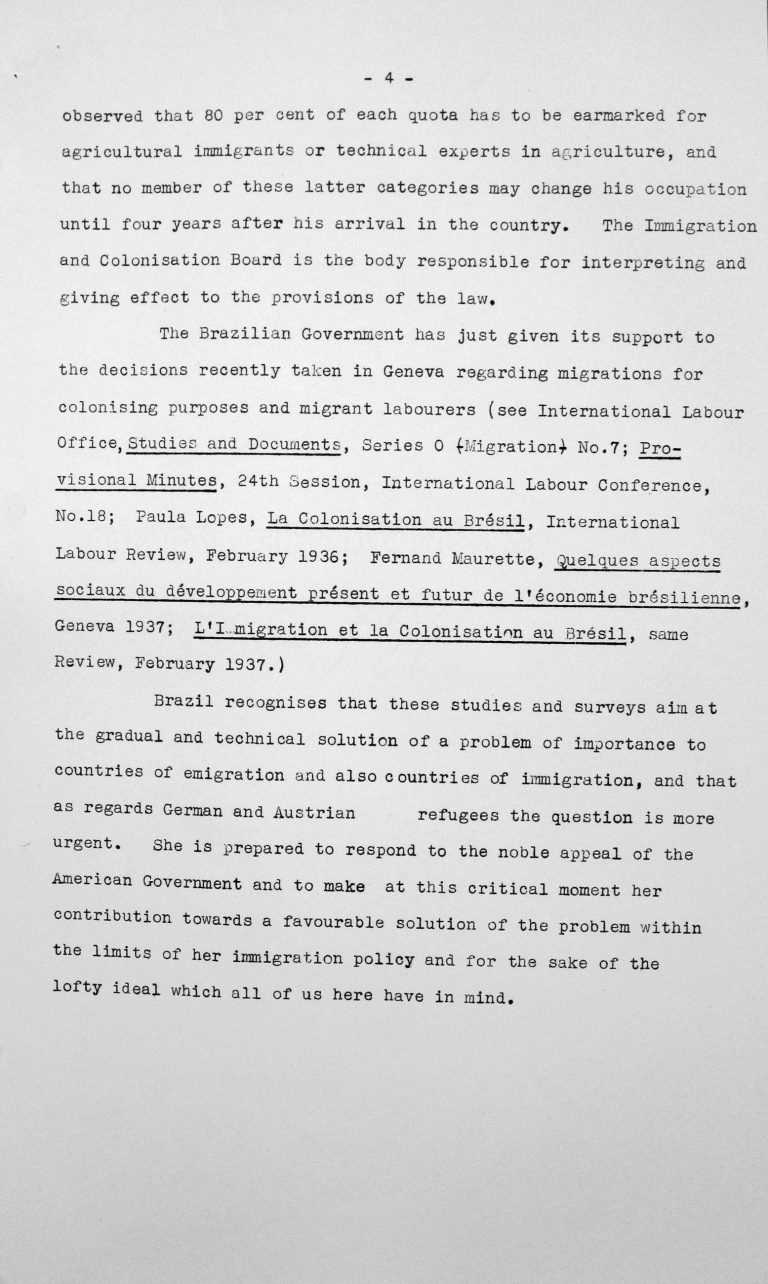

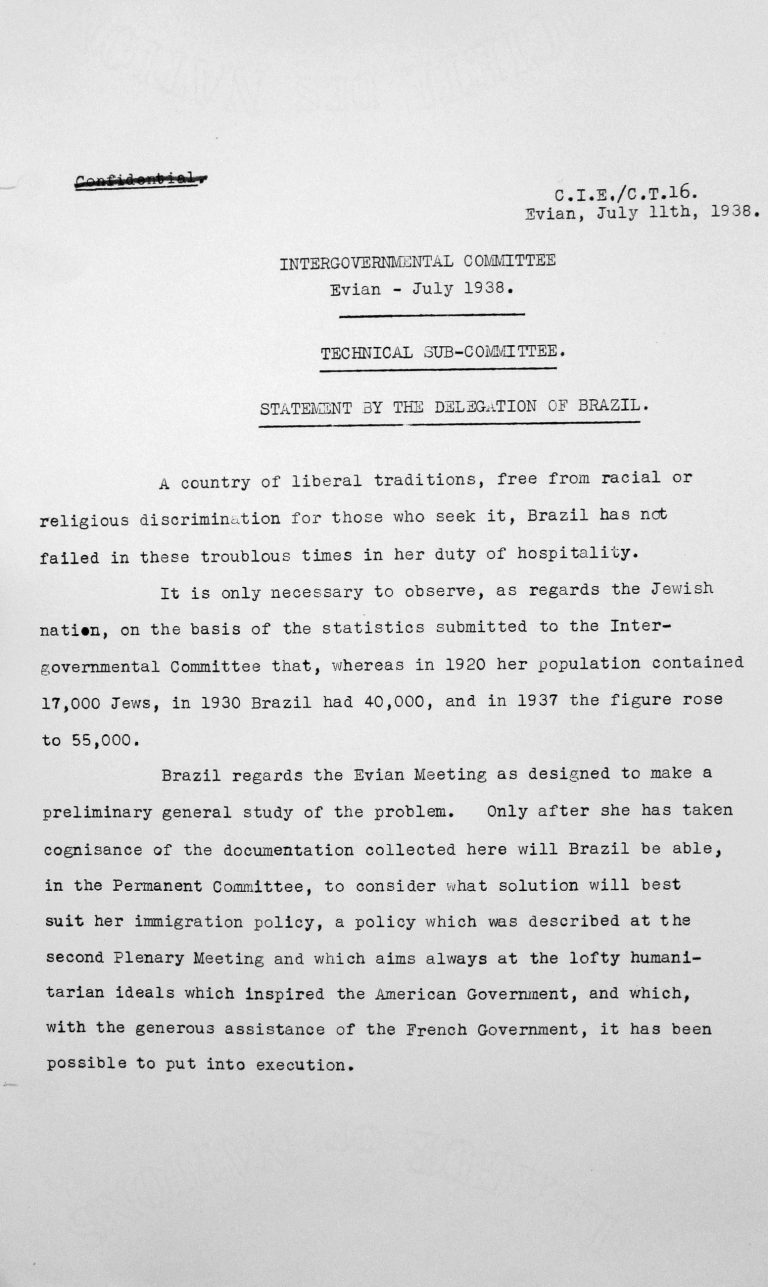

Statement by the delegation of Brazil to the Technical Sub-Committee, July 11, 1938

Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, NY

Statement by the delegation of Brazil to the Technical Sub-Committee, July 11, 1938

Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, NY